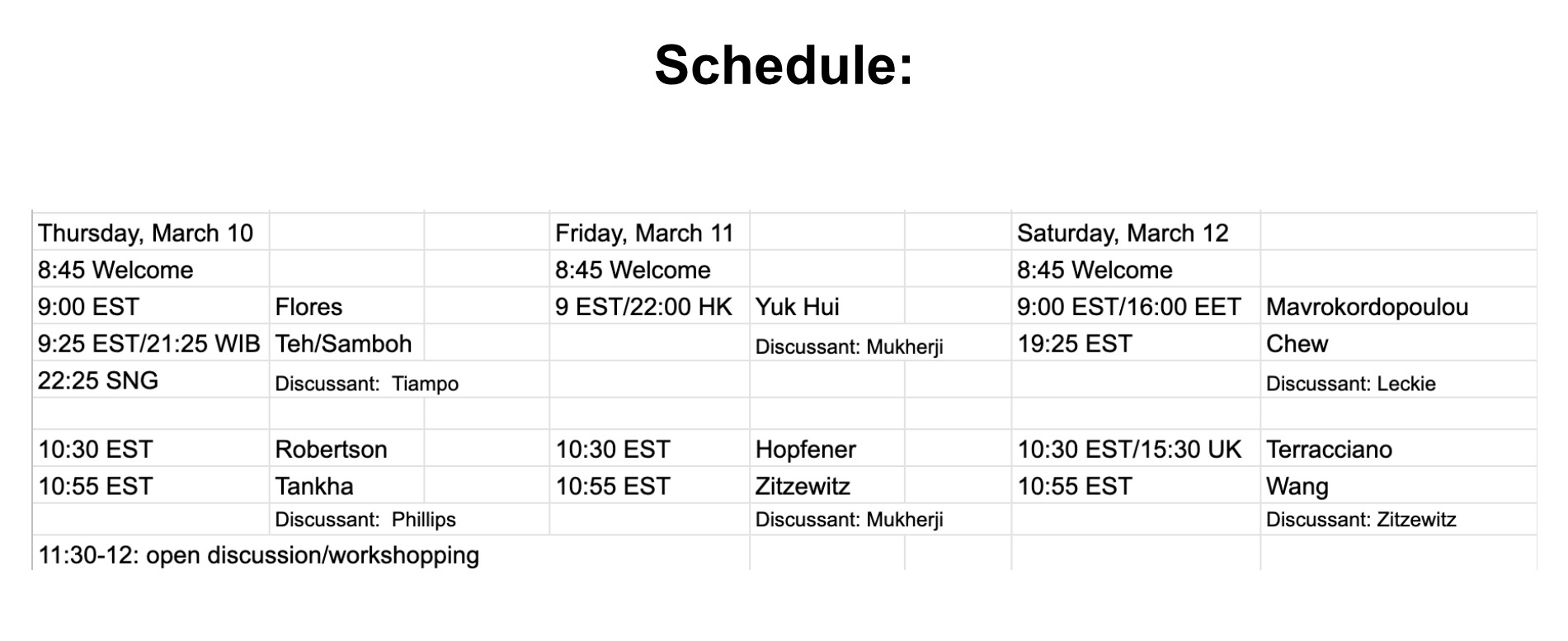

Virtual workshop organized by Birgit Hopfener (Carleton University) and Karin Zitzewitz (Michigan State University) at Carleton University, Institute for Comparative Studies in Literature, Arts, and Culture, Thursday, March 10-12, 2022, and supported by the Ruth and Mark Phillips Professorship in Cultural Mediations (ICSLAC, Carleton University).

Current global ecological, political and social crises, this workshop argues, have once again underscored the urgency of unlearning universalized modern Western frameworks in order to uncover the world’s cosmological, epistemological and ontological heterogeneity. Co-constituted with the modern Western frameworks that have conceptualized the world in line with colonial and imperial Eurocentric power structures, art history has primarily reinforced social, political and epistemological inequalities and hierarchies.

This session approaches the broader decolonial project through the category of temporality. Despite post-structuralist critiques of historicism, art and art history continue to be dominantly governed by modern Western linear models of time, underpinned by notions of modernization, rupture, avant-garde, revolution, causality, progress and the denial of co-evalness of what is conventionally called “non-Western art.” This session embraces the decolonial concept of the pluriverse in order to explore the potential of art and art historical scholarship to un/recover the multiplicity of temporal and historiographic frameworks.

The workshop seeks contributions that decolonize universalized historiographic frameworks and temporal concepts of art and art history through combinations of Western critique and epistemological research into art’s multiple relations to time and traditions of (hi)story writing/telling. We invite papers that critically engage with alternative temporal frameworks of art, different ways of relating the past to the present and the future or contributions that analyze art historiographies, object biographies, historiographic art or historiographic exhibitions as articulations and evidence of engagements with multiple and/or entangled historiographic traditions and models, and their related concepts and functions of art.

While the workshop organizers focus on modern and contemporary art, we welcome papers grounded in diverse art historical periods and forms of research, including museum and curatorial studies and the anthropology and philosophy of art.

The workshop will take place as an online event at Carleton University, Institute for Comparative Studies in Literature, Art and Culture on March 10, 2022.

To register, send email with your name and the subject line: “Multi-temporal Registration” to makenziesalmon@cmail.carleton.ca

Workshop Speakers:

Yuk Hui (keynote), Associate Professor, City University of Hong Kong

May Chew, Assistant Professor at the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema and Department of Art History at Concordia University, Montreal

Tatiana Flores, Professor of Art History and Latino and Caribbean Studies at Rutgers, and Director of the Rutgers Center for Women in the Arts and Humanities, The State University of New Jersey

Birgit Hopfener, Associate Professor of Art History, Ruth and Mark Phillips Professor, Confucius Chair, Carleton University

Barbara Leckie, Associate Professor in English and ICSLAC, Carleton University

Kyveli Mavrokordopoulou, PhD, art historian, affiliate researcher, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris

Parul Dave Mukherji, Professor, School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India.

Ruth Phillips, Professor Emerita, Carleton University

Carmen Robertson, Canada Research Chair in North American Indigenous Art and Material Culture at Carleton University

Akshaya Tankha, art historian of modern and contemporary South Asia, currently the Postdoctoral Associate and Lecturer at the South Asian Studies Council at Yale University

David Teh, Associate Professor at the National University of Singapore and Grace Samboh, curator currently pursuing a doctorate in Arts and Society Studies at the Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta.

Emilia Terracciano, Lecturer, University of Manchester

Ming Tiampo, Professor of Art History, Carleton University

Peggy Wang, Associate Professor of Art History, Bowdoin College

Karin Zitzewitz, Associate Professor of Art History and Visual Culture, Michigan State University

Abstracts:

Yuk Hui, Associate Professor, City University of Hong Kong

On the Varieties of Experience of Art

In his 1964 essay “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking,” Martin Heidegger claimed that cybernetics marks the end of Western philosophy and that it is necessary to begin thinking. What could this thinking, one that is probably no longer European and that which we might call post-European, look like? And in the context of this workshop, what could be the contribution of art to this possibility of thinking? Our questioning aims not only to affirm the aesthetic difference as a necessary step towards decolonization—because, in the past century, we have buried the varieties of experience of art by assuming and subordinating them to a particular definition of aesthetics, beauty and art; but also, to respond to the technological age in which we are living today, because art might remain the necessary path to access to “truth.” I suggest reopening the question of art such as what I attempted to do with the question of technology or technodiversity. François Jullien in The Great Image Has No Form, Or On the Nonobject Through Painting has attempted to show, through the comparison of Western painting and Chinese painting, that the former prioritizes form, and the latter undermines form, and therefore they present two absolutely different philosophical mentalities. In this talk, I want to take up Jullien’s critique, however, with a rather astonishing detour, I will contrast two seemly irrelevant experiences of art, namely Greek tragedy (which Authur Schopenhauer calls “the summit of the poetic art,” “the highest poetic achievement”) and Chinese shanshui painting (which has been also claimed to be the highest poetic achievement in Chinese art), in order to show, instead of simply reducing it to vague cultural differences, how could one understand the varieties of experience of art in terms of logic and sensibility, and how this exercise on aesthetics might allow us to reflect on the individuation of thinking today.

Tatiana Flores, Professor of Art History and Latino and Caribbean Studies at Rutgers, and Director of the Rutgers Center for Women in the Arts and Humanities, The State University of New Jersey

On the Impossibility of Global Modernisms

As Art History begins to take seriously the imperative to decolonize, one of the most vexing areas for its resistance to change the conventional periodization of art historical epochs. Even while acknowledging that spatial divisions like West and Non-West are deeply problematic as are geographic divisions per se, we continue to honor the “history” of our discipline’s nomenclature by insisting on temporality as a primary organizing category. The period commonly designated as “modernist” (roughly 1860 to 1960) is particularly difficult to divorce from Western ideals of progress as defined by both technological “advances” and also by heroization of artistic “innovation.” When the modernist moment attempts to open itself up to global narratives, its structuring undercurrent is a particular vision of the art of the West. In this paper, I revisit the reception of Impressionism in the 1910sand 20s in Mexico and in the United States to consider how an artistic idiom widely seen as retrograde at that moment became the basis for a radical rethinking on the democratization of art. My analysis exposes how, because of its championing of novelty and inherent Eurocentrism, the category of modernism obscures and suppresses artists and narratives that fall outside of its limited purview.

David Teh, Associate Professor the National University of Singapore and

Grace Samboh, curator currently pursuing a doctorate in Arts and Society Studies at the Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta.

Danarto: Notes from a non-binary Cold War

The work of the late artist, writer, designer and theatre-maker, Danarto (1940-2018) offers an exemplary study in the worldly scope of Asian modernism, and its capacity for corroding the worldly pretensions and telos of Art History. From early involvement with the multidisciplinary Sanggarbambucommune and the experimental Indonesia New Art Movement, through Cold War adventures in Europe and Japan, to his later literary successes, Danarto moved ceaselessly between disciplines, idioms and audiences. A conscientious objector to the ideological polarity of Indonesia’s ‘Golden Era,’ Danarto continued to confound both socialist and Free World-humanist versions of cultural nationalism, while keeping his distance from the accommodation of both ‘Islamic modernism’ and Javanese syncretism under the New Order. His oeuvre therefore illuminates the limits and inconsistencies of narratives of artistic progress, and queries the proper scope of the decolonial imperative. This paper introduces Danarto by reference to key works, differentiating his pluralism from other ‘tolerant’ positions in his national and transnational milieux.

Carmen Robertson, Canada Research Chair in North American Indigenous Art and Material Culture at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada

Beading Back and Forth: Upending Temporality through Knowledge Transmission

Knowing glass beads as active agents—as beings—proffers forms of analysis untethered from linear temporality and immersed in story. Such concepts inform the practices of Indigenous beaders in Canada yet remain at odds with conventional museological discourse. Analytical frameworks steeped in western philosophical traditions have long dictated limited understandings of art made by Indigenous peoples within the study of art histories, and as displayed and collected by museums and galleries. Despite museological conventions that reproduce entrenched processes of objectification and linear classifications, Indigenous aesthetics based on relational and dialogical epistemologies has recently gained traction within the study of Indigenous arts in a Canadian context. Focusing specifically on how glass beads and makers of Indigenous beadwork from the past and present grow communities and form collaborations with both living and ancestral kin in support of future generations of Indigenous makers in the prairie region, this analysis aims to help upend conventional colonial structures of knowledge entrenched in institutions.

Akshaya Tankha, art historian of modern and contemporary South Asia, currently the Postdoctoral Associate and Lecturer at the South Asian Studies Council at Yale University

The Naga memorial monument and the aesthetics of Indigenous presence in postcolonial South Asia

Since 1990, memorial monuments to Naga nationalist soldiers have become visible on highways in Nagaland, an Indigenous and Christian state in northeast India that was home to an armed movement for political autonomy from the Indian state from 1953 to 1997. But they have failed to garner scholarly attention due to the persistence of salvage ideas of “tribal culture” as archaic or their regard as passive illustrations of political claims to territory ruptured from “tribal culture”. This paper proposes to show that an art historical account of the monuments reveals that their political significance today is tied to the ever-changing corporeality of land in Indigenous lifeworlds. I will argue that this illuminates the plural and layered temporality of Indigenous art and aesthetic politics amidst their marginalization by the postcolonial state, enacting an aesthetics of endurance and emergence that resonates with what North American Indigenous scholars call “survivance” and “resurgence”.

Birgit Hopfener, Associate Professor of Art History, Ruth and Marks Phillip Professor, Carleton University

Re-framing contemporary Chinese art through the lens of “endlessness” buxi不息 A contribution to a pluriversal critical framework of contemporary art

Institutionalized contemporary art history, theory and aesthetics continue to be dominantly rooted in the universalized Euro-American modern-postmodern genealogy, its respective temporalities and discourses centered around critiques of “Western representationalism” (Karen Barad). Despite the global turn and a new understanding of contemporaneity as a critical and not a temporal category anymore (Peter Osborne, Terry Smith), the multiplicity of contemporary art’s art historical temporalities, and its diverse and often transculturally entangled aesthetic and critical frameworks have not been sufficiently considered when attributing status and meaning to contemporary art.

Invested in the realization of a decolonial and worlded contemporaneity of “cognitive justice” (Boaventura de Sousa Santos) and co-eval participation (Johannes Fabian) this paper seeks to contribute to the creation of a pluriversal critical framework of contemporary art. Such a framework critiques the assumption that “art theory has a natural home in the Euro-American context” (Parul Dave Mukharji). It seeks to undo the Western “temporal normativity” (Rolando Vasquez) by attending to the temporal and cultural historical complexity of contemporary art through aesthetic, epistemological, ontological and cosmological “re-framing” (David Joselit). The exhibition “Continuum – Generation by Generation” curated by the contemporary artist-cum-curator Qiu Zhijie in 2017 for the Chinese pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennial is an exemplary case study in this regard. This paper examines how the show mobilized “endlessness” buxi 不息, a traditional Chinese concept central in Chinese process cosmology and, according to the curator, a key “operating mechanism in Chinese art.” The paper critically examines how the show and the artworks engage with a concept of art that is committed and obliged to understand, articulate, navigate and mediate world and life conceived as impermanent and endless (buxi) transformational process. It also shows how the meaning of contemporary curatorial and aesthetic strategies change if they are re-framed through the lens of buxi.

Karin Zitzewitz, Associate Professor of Art History and Visual Culture, Michigan State University

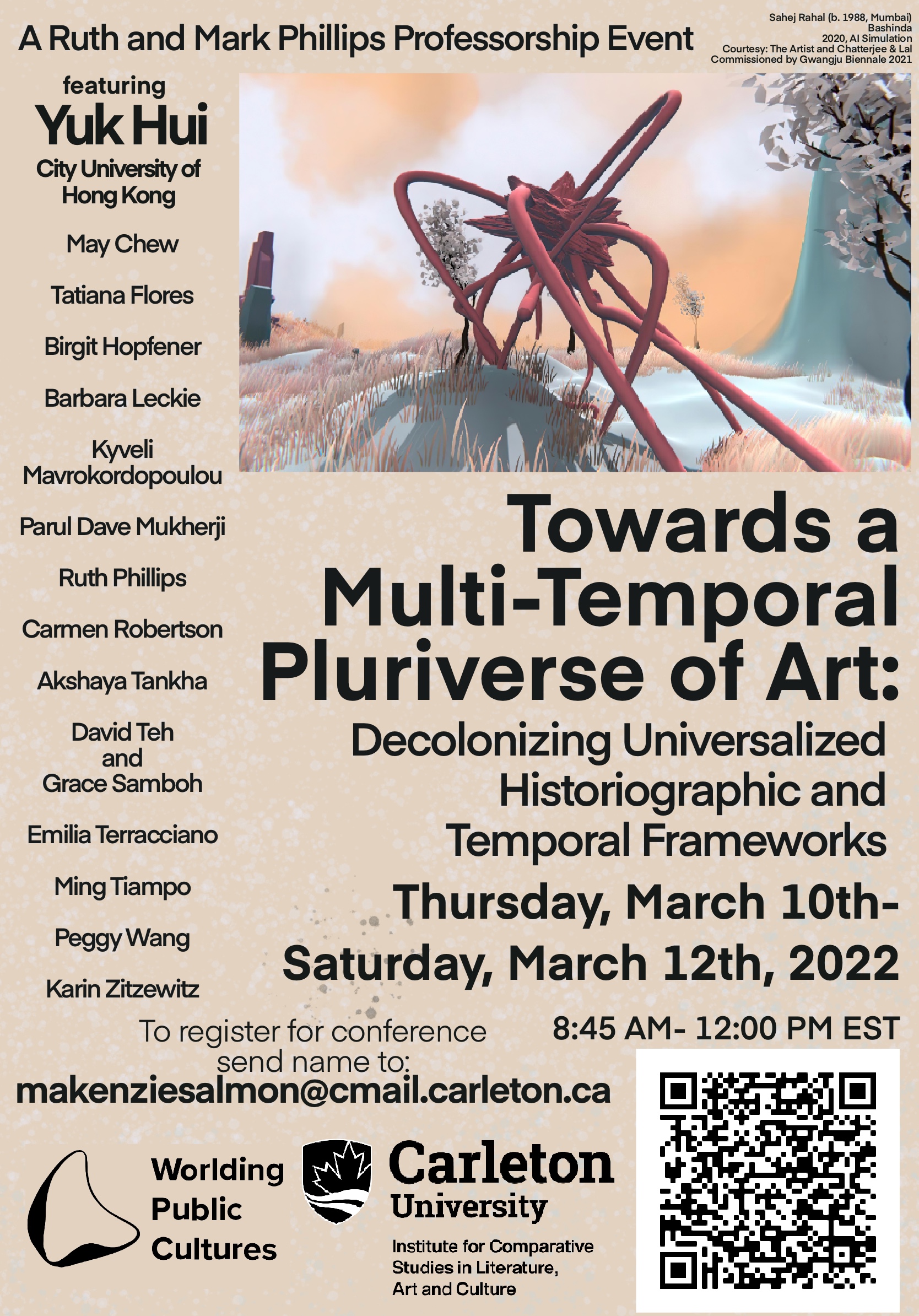

Sahej Rahal’s Bashinda and the temporality of caste

This project presents Indian artist Sahej Rahal’s Bashinda (2020), an AI-driven, interactive simulation that follows a twelve-armed, roving cephalopod with a body like a rock formation as it navigates through a grassy landscape. Meaning dweller, denizen, inhabitant, and sometimes citizen in Hindi-Urdu, Bashinda gestures at once towards a sci-fi-style future and an evolutionary beginning of life. It provides an incipient counter-narrative to the dominant mythological explanation of human life in Hindu tradition. As told in the Laws of Manu, that story imagines the origins of humanity and of caste as simultaneous, and it understands moral conduct, or dharma, as delimited by classification at birth. As Bashinda explicitly discusses, Manu’s caste cosmology is considered transhistorical by India’s autocratic Hindu nationalist regime, which forcefully overrides progressivist claims to low-caste and Dalit emancipation from caste as an outmoded form of discrimination. In other words, caste conflict is driven, in part, by incommensurable temporalities. This artist project will focus on the uncanny temporalities of Bashinda in order to explore how Rahal’s work with artificial intelligence is capable of engaging questions of time in new and potentially radical ways.

Kyveli Mavrokordopoulou, art historian and curator, currently finishing a PhD at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris

“Not the End”: Enduring nuclear temporalities in the work of Eve Andrée Laramée and Bonnie Devine

Casualties of nuclear technologies are not immediate, and the populations that bear the most significant burden are too sparse to be noteworthy, especially in the case of uranium mining industries. Shaped by forms of settler colonialism –the US and Canada mine on Indigenous and First Nation reservations –effects of radioactive exposure produce slow, recursive forms of nuclear suffering as illness may take up to 30 years to manifest. This paper argues that the forward-looking temporality of progress, essential to the nuclear project, is inadequate for grappling with the ongoing violence that rendered some populations anachronistic and disposable. Halfway to Invisible (2009), an installation by Eve Andrée Laramée (1956) and Rooster Rock. The Story of Serpent River(2002), a video by Bonnie Devine (1952), addresses the deleterious, enduring consequences of uranium mining for nuclear workers in New Mexico and Ontario, respectively. Drawing on what anthropologist Felix Ringel calls practices of endurance, a practical politics against the progress narrative and the biopolitical ordering of life, I suggest that Laramée and Devine gesture towards an active process of remaining, centring on the open-ended temporalities of radioactive exposure. As the final scene of Devine’s video puts it, this is “Not The End”.

May Chew, Assistant Professor at the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema and Department of Art History at Concordia University, Montreal

Reorienting Immersion through Decolonial Aesthetics and Praxis

This paper critically maps the development of immersion in Canadian exhibition history and media theory alongside the consecration of Canada’s “technological modernity” in the mid-twentieth century. This critical genealogy illuminates the ways that immersion has been mobilized in Canadian settler discourses of technological conquest, modernity, progress, and liberal self-hood and agency. It then examines how contemporary art practice can upend these colonial paradigms by drawing on diverse immersive formats that propose alternate—Indigenous and diasporic—models of decolonial relationality, embodiment, and futurities. Challenging settler paradigms of immersion, artists like Lisa Jackson and Camille Turner indicate a politics of self-location, where being embedded in landscape facilitates relationality over visual dominance. This paper explores how their immersive works create space for insurgent embodiments and conjure the material and imaginational processes of re-worlding as decolonial praxis.

Emilia Terracciano, Lecturer, University of Manchester

Animal, vegetal, mineral, human: Simryn Gill’s temporal scales

This paper considers the relationship between the concepts of time and scale in the practice of artist Simryn Gill (born Singapore 1959). The practice of shaping standards in relation to the temporal activity they pace is entrenched. Rubber trees in Malay plantations were planted in grid to accelerate sap collection. This paper investigates Gill’s temporal understanding of scale by focusing on ‘cosmopolitical’ sites. By Gill’s own admission, the relationship between space and time is always opaque and exposes the closed, circular process of production and self-representation typical of measurements. Unlike the openness of scale whose evaluation is relative because it rests on a comparison determined only by the terms involved, size is codified by shared historical measuring practices which relate to the authority wielding such practices. Highlighting the distinction between scale and size, as well as exposing the analogical, non-systematic process, and multi-temporality in her practice, Gill photographs parts of her artworks while wearing and embodying them.

Peggy Wang, Associate Professor of Art History, Bowdoin College

Rethinking “tradition” and technology in Qiu Anxiong’s New Book of Mountains and Seas

From 2006 to 2017, Qiu Anxiong produced a trilogy of animations called the New Book of Mountains and Seas. The title references a text compiled before the second century CE which functioned as an encyclopedia of strange beasts and phenomena. Like the original bestiary, Qiu’s films are populated with odd zoomorphic creatures. They feature in distinctly dystopic narratives: in Part I, the global energy crisis; in Part II, questionable “advancements” in the name of science; and, in Part III, the slippage between real and virtual worlds as facilitated by digital networks. More than just a whimsical play on zoomorphic machines, and more than simply an updating of “tradition,” Qiu’s creatures arrive through a particular worldview: he imagines the world as if seen through the eyes of someone living thousands of years ago, alive during the time of the original Classic of Mountains of Seas. After all, to a person from ancient times, things that move—cars, airplanes, submarines—would certainly be regarded as alive. But, rather than casting this subject-position as primitive and backwards, Qiu mines the generative possibilities of adopting this new logic in perception. This paper takes seriously Qiu’s investment in exploring temporal frameworks as challenges to contemporary limitations on ways of understanding time and the implications of this on knowledge production. Indeed, we can see how his animations question how references to “tradition” and assumptions around “technology” have been wrapped up in restrictive ideologies of progress. Qiu’s artistic choices shed light on how his animations serve as meditations on time and space, particularly informed by his own cross-cultural experiences before the creation of the trilogy, and his experiences with technologies for animation during their production.