By Ty Burke

Photos by Adam Landry

Road salt helps keep our roads and sidewalks safe during the icy winter months. But it also harms aquatic ecosystems, corrodes vehicles, and reduces the lifespan of infrastructure.

“Road salt is used everywhere. Not only on roads and highways, but sidewalks, parking lots, bike trails, walking trails – and even your front step,” says Mitchell Lawlor, a PhD student in Carleton’s Advanced Road & Transportation Engineering Lab (ARTEL).

“The need for de-icers is not going away in northern climates. Road salt reduces collisions and increases transportation efficiency; it is essential to the functioning of the Canadian economy. But it also has harmful effects, and alternative de-icers could be an improvement.”

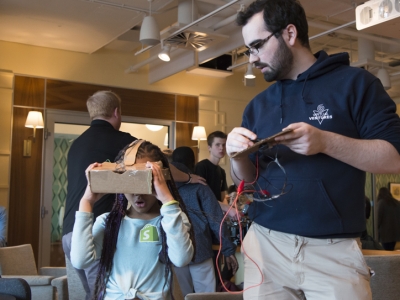

PhD student Mitchell Lawlor and Professor Kamal Hossain measure the friction of a campus walkway using a SlipAlert testing system. To determine the relative slipperiness of a surface, the cart is pulled up a ramp and released, allowing it to roll to a halt and provide a value that indicates either a low, medium or high risk of slip.

“They might require a greater initial investment, but could save money in the long run. If you can eliminate corrosion, you can increase the lifespan of vehicles and infrastructure like roads, bridges, and sidewalks.”

Lawlor is evaluating the effectiveness of an innovative alternative de-icer produced by STAR’s TECH, a South Korean company. Its ECO-ST de-icer uses an unusual additive to reduce the negative impacts of de-icing – an extract from an invasive species of starfish. South Korea’s government purchases invasive starfish harvested by local fishermen, who collect them from the country’s coral reefs. Researchers and private companies then try to use those starfish for commercial applications. In this case, a chemical engineering group developed a de-icing material that can help adsorb chlorine.

They provided six samples to ARTEL, and so far, the testing results have been promising. In ice melting and penetration tests, ECO-ST was on par with road salt. That part was expected, because ECO-ST uses a sodium chloride-calcium chloride base that is chemically similar to road salt. But ECO-ST was also less corrosive than road salt.

“The corrosion aspects were almost completely wiped out, but the ice melting potential was retained,” says Lawlor. “The extract adsorbs the chloride in the brine produced, and that is a really big thing. If we can reduce the chloride content, we can reduce rust to vehicles and damage to concrete infrastructure.”

“It will also help our water systems. High chloride levels in our lakes and rivers leads to the growth of algae, which disrupts the ecosystem, and adds to treatment requirements for drinking water. It would be extremely beneficial if we could reduce this.”

Though the first study on ECO-ST’s corrosivity yielded promising results, more research is required. Going forward, Lawlor will study the de-icer’s effects on the degradation of asphalt and concrete, and conduct lab tests on its efficiency.

Lawlor and Hossain are currently testing two different types of STAR’s TECH ECO-ST (the company’s base product and another the has an added 1.5% of starfish extract) and a local Ontario alternative “Fusion” deicer from EcoSolutions, in comparison with standard sodium chloride that is regularly used on roads and walkways.

“If governments or private industry see results in a side-by-side test, they may be more willing to support further research into how we can create something like this in Canada,” says Prof. Kamal Hossain of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, who is co-supervising Lawlor’s PhD research alongside Prof. Jennifer Drake, the Canada Research Chair in Stormwater and Low Impact Development (Tier II). “There is potential that this material exists in some part of the natural environment here.”

But it is important to thoroughly test alternative de-icers before they are widely deployed. To replace road salt, a de-icer needs to be both safe and effective.

“The biggest thing right now is to get field tests done. We need real-world scenarios to make sure it works, and the feasibility of that dictated by external conditions,” says Lawlor. “I can’t control when it snows or how much snow we get. But the sooner we can get testing complete, the better. We will be focused on that until early spring, and that is when we will dive deeper into the laboratory work.”

Thursday, January 18, 2024 in Civil, Environmental, Feature Stories, Graduate, Industry Collaboration, Research, Water

Share: Twitter, Facebook