How Russian Television Primed the Public for War – by J. Paul Goode

Following Russia’s invasion, a vigorous debate erupted over whether ordinary Russians support or oppose the war, with a great deal of attention focused on the kinds of information presented to them via broadcast media. It is well known that most Russians get most of their news from television—a fact that likely will increase with the ongoing crackdown on foreign news and social media. That Russian broadcast media is now state-owned or state-controlled is a constant refrain in studies of Russia’s domestic politics, and particularly in past explanations for the failure to mobilize and coordinate opposition protests. To what extent can we determine that state control of television played a role in preparing Russians for war?

A couple of caveats are in order before continuing to the data and analysis. First, this research should not be interpreted as suggesting that Russians are “zombified” by television, nor does this research measure or justify the Russian public’s ambivalent reception of the war. However, we can observe whether (or how) the Kremlin used television to advance its objectives, as well as the means by which it pursued those objectives. In turn, these kinds of findings provide some insight to the public ambivalence that stems from the regime’s domination of discursive space in Russia.

Second, the goal of this approach is not necessarily to re-create Russians’ viewing habits, though one might reasonably assume that more frequently mentioned topics are more likely to have been viewed or noticed. Rather, the frequency and distribution of topics over time reveals the extent to which state-controlled television presented a coordinated campaign. In the absence of reliable public opinion data in war-time Russia, such an approach further suggests insights about the ways that Russians were prepared for, and reacted to, the onset of war.

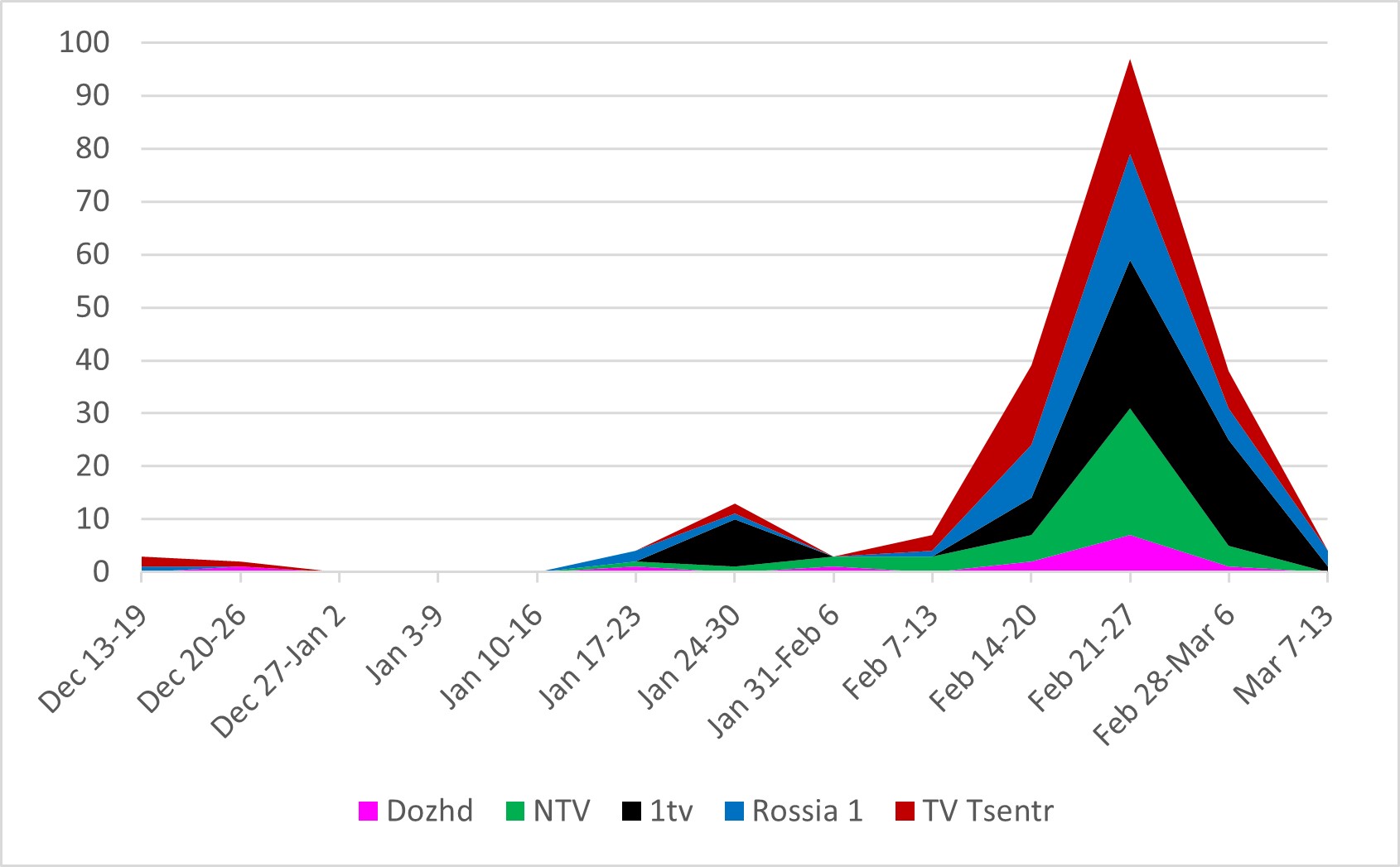

The data for this study are drawn from the Integrum Profi television broadcast transcripts, which were analyzed on a week-to-week basis from December 13, 2021 through March 13, 2022. The week of December 13 was chosen as a starting point just before Putin initiated a crisis in relations with Russia with the issuance of his ultimatums to the US and NATO, hence a coordinated media campaign in Russia might also be observed from this time. Five channels were chosen for analysis: the state-run channels Pervyi Kanal (1tv) and Rossiia 1, the pro-government NTV (owned by Gazprom Media), Moscow’s public television station TV Tsentr, and the independent Dozhd TV (which ceased operation on March 3, 2022).

Beginning with Russia’s claim that its invasion was intended to stop an alleged genocide in eastern Ukraine, one would expect to find at least somewhat constant signaling of a genuinely humanitarian concern from the start of the crisis in December 2021 through the invasion of Ukraine and the early stages of war. In reality, genocide barely rated mentioning save for a small spike by the state-owned Pervyi Kanal in late January (see Figure 1). By the time the decision to go to war had been taken, mentions of genocide soared on state-owned and pro-government television channels. The effect is even more pronounced when looking at online press agencies, which provide the raw materials for posting and circulating on social media. We see a similar pattern more generally on Russian websites, it is worth drawing attention to the number of sites that are driving these mentions: for the week of March 7-13, for example, just 3 websites drove 40% of mentions of genocide.

Figure 1: Mentions of “Genocide” on Russian TV, Dec 13-Mar 13

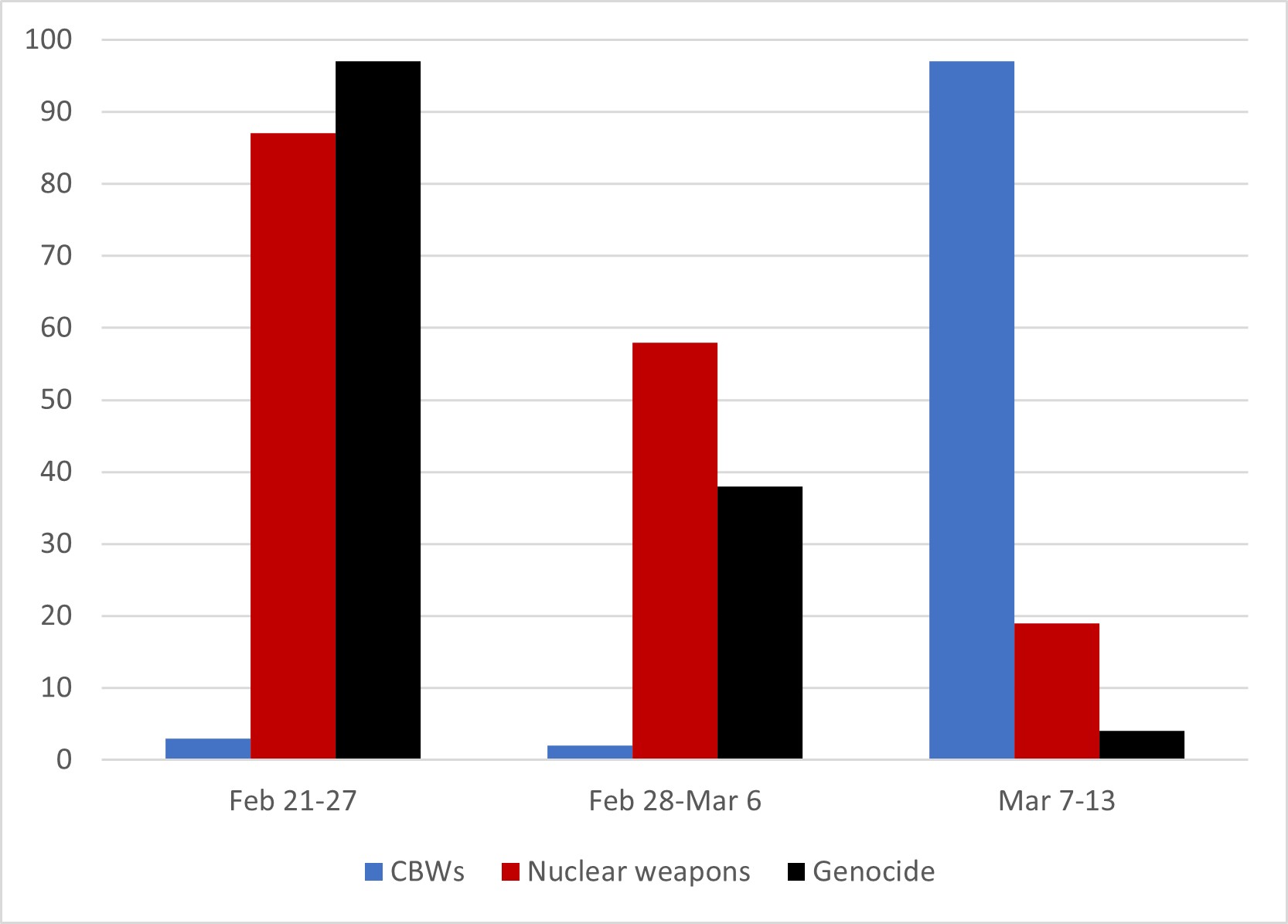

Further evidence of the instrumental mobilization of humanitarian concerns is found in the shifting narratives in the weeks immediately following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (Figure 2). In the two weeks following the start of the war, “genocide” almost completely disappeared from mentions on Russian TV. A new narrative emerged concerning fears that Ukrainian nationalists might get ahold of nuclear materials to make dirty bombs, but this quickly dissipated after the messy and alarming seizure of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant by Russian forces. Instead, that narrative was quickly replaced by new claims about the purported threat that increasingly desperate Ukrainian forces might resort to using (or had already planned to use) chemical and biological weapons.

Figure 2: Shifting Narratives on Russian TV, Feb 21 – Mar 13

In short, it is difficult to view Russia’s humanitarian justifications for invading Ukraine as little more than cynical manipulations that served to put such terms and discourse into circulation, providing viewers with a regime-friendly lexicon to frame and discuss the war.

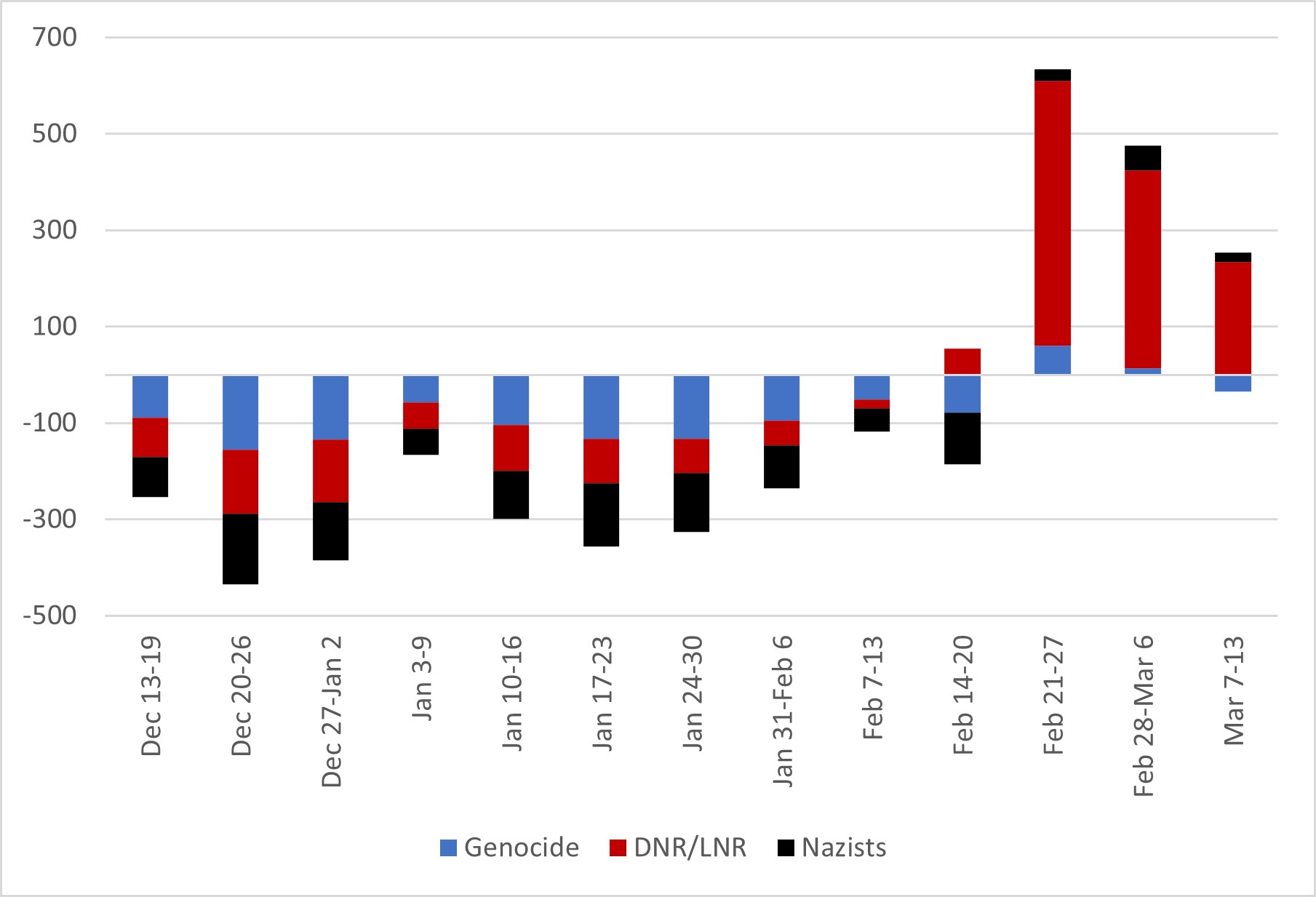

While the patterns of mentions on Russian television are striking, how likely is it that they were noticed by Russian viewers? As the weather is perhaps the only thing that is reported objectively and consistently across all channels, it is a helpful measure of what constitutes normal background noise on Russian television. I used a simple measure of the number of mentions of war-related topics relative to the reporting of the weather. The assumption guiding this approach is that topics mentioned less often than the weather probably are less likely to be noticed, while those mentioned more frequently than the weather are more likely to be noticed. With regard to genocide, the separatist republics in eastern Ukraine (the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics), and Nazis, none of those topics warranted more mentions than the weather on Russian television until just before the invasion (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Mentions of Genocide, DNR/LNR, and Nazi vs the weather on Russian TV, Feb 13 – Mar 13

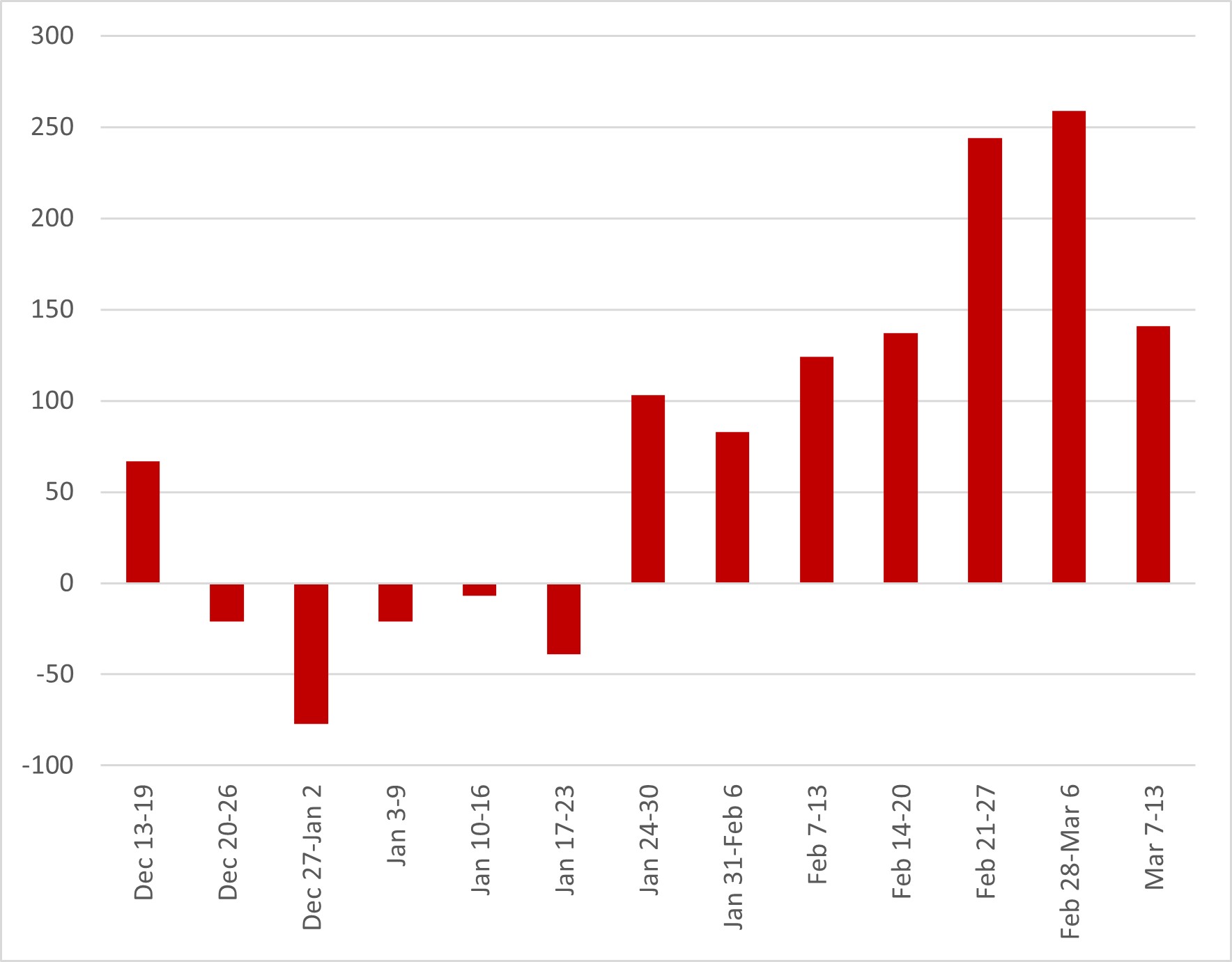

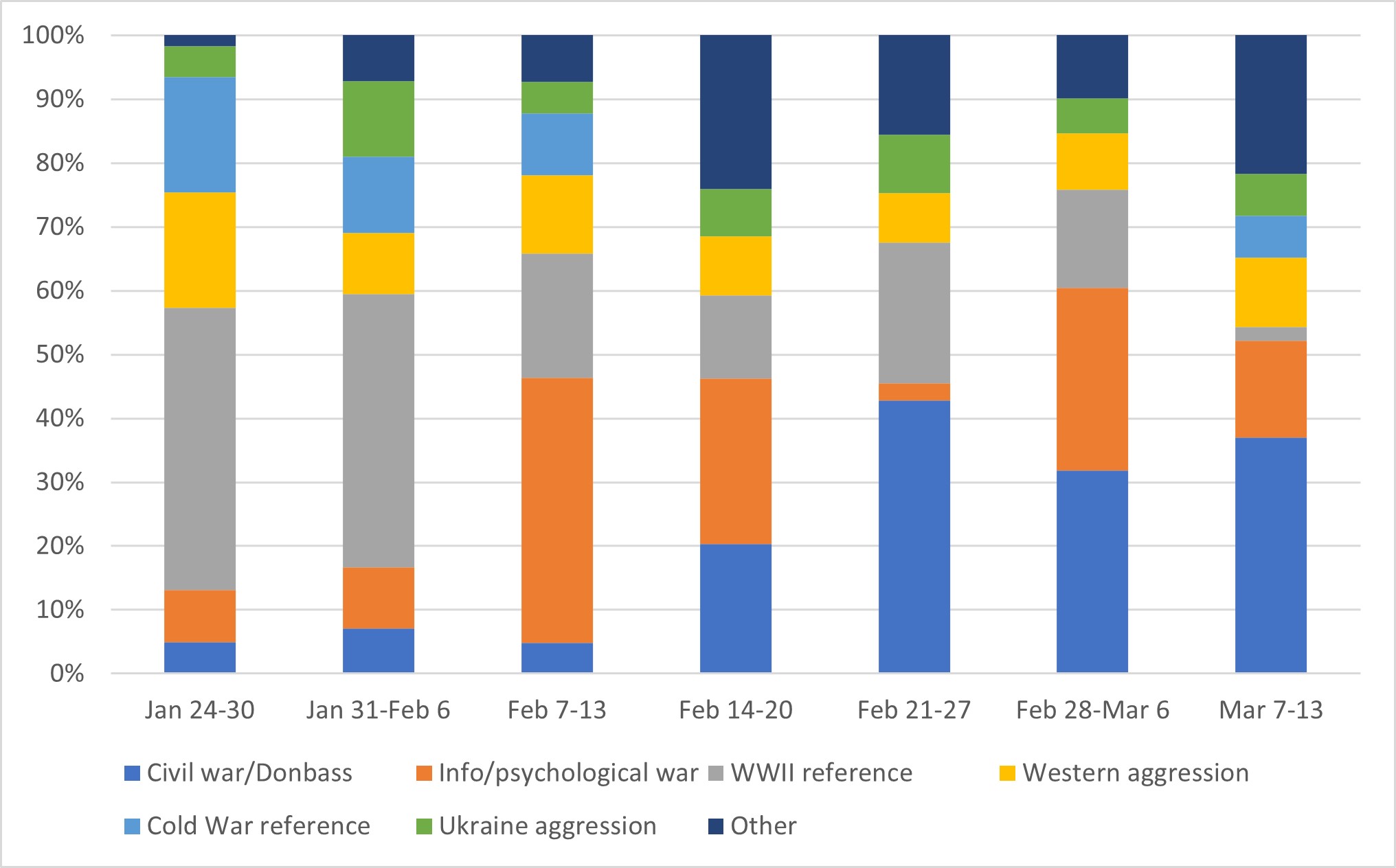

However, somewhat interesting is Russian TV suddenly elevated mentions of war in all sorts of ways from late-January, none of which were initially related to Ukraine (Figure 4). Looking closely at the various ways that war was mentioned from January 24 through March 13 (Figure 5), one observes lots of mentions in reference to the Great Patriotic War in mid- to late-January. This may be considered on-brand for the Kremlin, which has turned the memory of the war into a cornerstone of the regime’s legitimation. One also finds references to the Cold War and Western aggression (past and present) in roughly equal proportions. By February, this “war talk” expanded to include information warfare, particularly in mocking the West’s “mythical Russian invasion” of Ukraine—only to disappear after Russia actually invaded Ukraine. The prevalence of “war talk” in the run up to the invasion is ironic given that the Kremlin refers to its invasion of Ukraine as a “special military operation” and has effectively banned any reference to the war or invasion online or in the press. Nevertheless, it may have normalized the notion of Russia’s being at war in advance of the invasion.

Figure 4: Mentions of War vs the weather on Russian TV

Figure 5: Mentions of “War” on Russian TV, Jan 24-Mar 6, 2022

In conclusion, Russian television primed viewers for war with steady doses of “war talk” prior to the invasion. It reminded Russians of past victories as well as betrayals. State-controlled television deftly merged this “war talk” with narratives about Western and Ukrainian aggression before fully joining the war effort by advancing claims about the prevention of genocide and fighting fascism. Russians may not have sought war with Ukraine, but the justifications resonated with television-promoted world views that made Western and Ukrainian treachery appear both plausible and lamentable. Once these narratives were put into circulation, the Kremlin no longer had to convince the public but instead activated new narratives in each week of the war to justify its invasion of Ukraine.

~ J. Paul Goode

McMillan Chair in Russian Studies and Associate Professor, Institute of European, Russian and Eurasian Studies, Carleton University (paul.goode@carleton.ca)