Iconoclasm

I teach a survey of medieval architecture and art, and this week I reached the period known as Byzantine. It’s a subject that I love teaching, because it gives me an excuse to talk about some of the most remarkable architecture ever built. But this year, it has an added poignancy, for reasons that I could never have foreseen. Last week’s horror in Paris gave events thirteen centuries earlier a very contemporary aura.

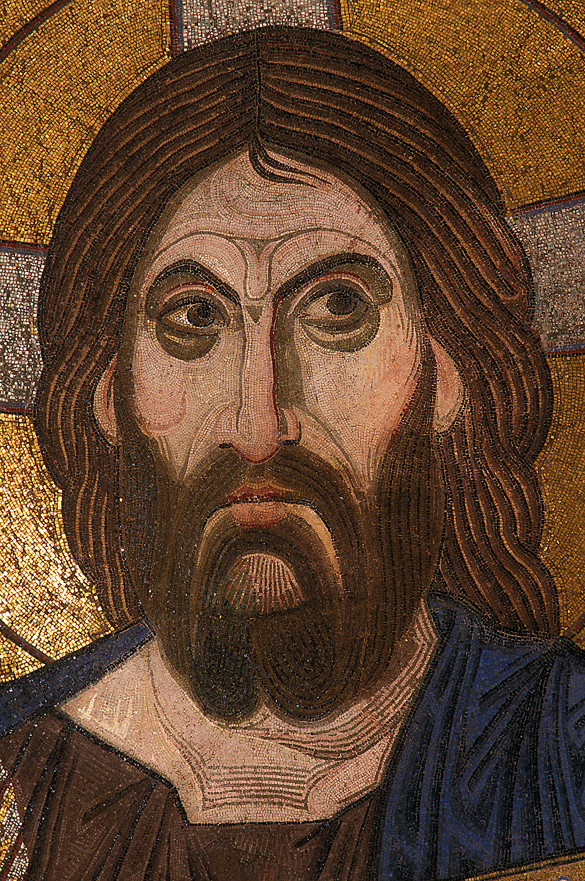

One episode that I briefly deal with when discussing Byzantine history is a movement known as iconoclasm. The Iconoclasts believed that all religious images were idolatrous and had to be suppressed. They were opposed by “Iconodules”, who believed that Christ’s human, corporeal nature validated pictorial representations of sacred subjects.

The debate was an intellectually lively one, at least at first. Plenty of scholars today are of the opinion that the Iconodules had the stronger case, but the reality is that the Iconoclasts gained the support of some key allies – in particular Emperor Leo III and his son Constantine V – and, just as importantly, of the army. Iconoclasm became official policy in the Byzantine Empire for most of the years between roughly 754 and 843.

What followed was an orgy of destruction, in which countless artworks were obliterated and their defenders ruthlessly persecuted. As is usual in ideological warfare, there was no room for doubt or compassion. The iconoclasts knew they were right, and no further discussion was needed. Compromise was unthinkable. Dissent was a disease to be annihilated.

I don’t want to belabour the parallels between eighth-century Constantinople and what happened January 7 in Paris. But the battle to control others’ images – and through them, their thoughts – is a very old one. It is sobering to realize that it is still being fought. If James Joyce was right when he said that history is a nightmare from which we are constantly trying to awaken, then last week was a reminder of how soundly asleep we remain.