Wisdom

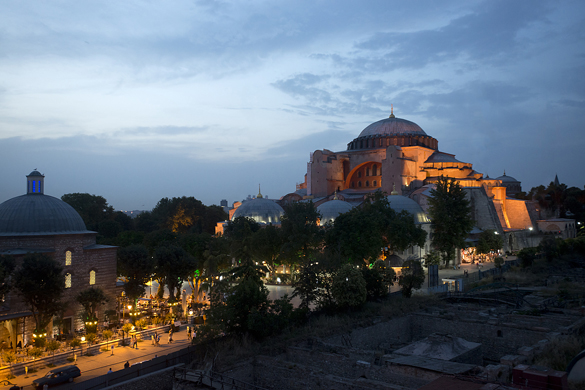

In an earlier blog, I mentioned that the Byzantine section of my medieval course gives me a chance to talk about some truly amazing architecture. Perhaps the most amazing of all is the church dedicated to “Holy Wisdom” – the Hagia Sophia – built in Constantinople (now Istanbul) between 532 and 537. And, like the eighth-century debate about iconoclasm I discussed in that earlier blog, its turbulent story is still unfolding.

One of the most innovative and awe-inspiring spaces ever created, the Hagia Sophia is also one of the biggest political footballs ever to be kicked around. It was designed not by an architect, but by a geometer (Anthemius of Tralles) and a physicist (Isidorus of Miletus). Their patron, the Emperor Justinian, had just come within a heartbeat of losing his crown and life during the Nika riots. The dust eventually settled and Justinian prevailed, but he needed to re-build his battered capital city. That re-building wasn’t just a case of replacing demolished buildings. It was also about creating compelling public symbols that would prove that the Emperor was back in control. The biggest and most important of these symbols was to be the imperial church – the Hagia Sophia.

So, right from the start, the Hagia Sophia was conceived not just as a staggeringly beautiful building (although it certainly is that), but as a piece of political propaganda. That propaganda function has never completely disappeared from its job description. After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, Sultan Mehmed II knew he had inherited one of the most venerated churches in the world. Instead of demolishing it as a symbol of the old regime, he converted it to a mosque. The changes to the fabric of the building were fairly modest, the most obvious being the addition of four monumental minarets to the exterior. Thus, Justinian’s symbol of triumph over rebellion became a symbol of the triumph of Islam over Christianity.

The Hagia Sophia remained a Mosque until 1935, when Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, converted it into a museum. Like the building’s earlier transformations, this was very heavily loaded with symbolism. Rather than proclaiming the triumph of an Emperor or of a faith, the Hagia Sophia became a symbol of the triumph of the secular, republican values of the new Turkey. Visitors came not to worship, but to marvel at the engineering and craftsmanship of this most remarkable example of architectural art.

Today, there is a vigorous lobby to turn the Hagia Sophia back into a mosque. This isn’t because more mosque space is needed – the huge Blue Mosque, just a couple of hundred metres away, is far from full. It’s another appropriation of the building for symbolic purposes – in this case, to announce the ascent of religion in the now not-so-secular republic.

How this would affect the access of non-worshippers to this incomparable monument is unknown. How it might threaten the survival of the building’s remaining Christian mosaics, dating from the 13th century, is also quite troubling. Whether turning the clock back 500 years on a 1500 year-old building is an act of ‘restoration’ or vandalism is another awkward question.

It may be the Hagia Sophia’s fate to be a political football, but I find this latest kick quite worrying.