Reflections from the Tour Guides, Part 1

churches.

We are continuing our series of student blogs with a number of reflections on the “Small Modernisms” symposium, a public event held at the Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre on May 12-13, 2022. The event was organized by Professors Michael Windover and Dustin Valen. The blogs were written by undergraduate students in the History and Theory of Architecture and Art History programs in Carleton’s School for Studies in Art and Culture.

By Moira Power

Earlier this year, professors Michael Windover and Dustin Valen approached me with an offer that neither I, nor fellow student Carson McLaren, could possibly refuse: an opportunity to challenge architectural historiography. Carson and I would not only attend but also take part in an inclusive and captivating symposium entitled “Small Modernisms.” Our task was to help challenge dominant architectural discourses, which tend to focus on the work of cisgender white men, by instead shedding light on underrepresented and silenced voices. From May 12–13, we would disregard names like Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, and Louis Sullivan, in favour of names unbeknownst to us at the time, like Tela Purcell, Sandy Yep, and Les McAfee.

The organizers asked Carson and I to research, curate, and conduct an architectural walking tour of the 110-year-old building where the symposium was going to be held. As a student of art and architectural history, researching buildings and putting my research into words was not a foreign concept to me, but this experience was unique. The walking tour of the Carleton Dominion-Chalmers Centre (CDCC) we were asked to compose wasn’t about the architect, Alexander Cowper Hutchison. Neither was it about Romanesque Revival churches, nor about how the building’s architect used a steel structure to create soaring interior spaces, in a modern take on classicism. On the contrary, “Small Modernisms” set out to highlight often overlooked aspects of architectural history: how did individuals use the church building? For what purposes? And what role did the church play in shaping postwar Canadian society?

Planning the tour wasn’t easy. The pandemic halted ongoing digitization efforts at the CDCC’s archives, leaving records of the past to idle in storage. Thankfully, the director of the CDCC, Mara Brown, wouldn’t let that to stop us. With her help, we gathered the resources we needed to complete our research. This research phase was important since Carson and I wanted to connect spaces in the CDCC to the stories of people who used them. With over a century of history to cover, we decided the best way to produce an engaging, coherent tour was to divide the spaces and focus on stories that fell under two broad themes: “The Church as an Extension of the Domestic,” and “The Church as an Educational Space for Youth.”

In focusing on youth and education, I was confronted with a multitude of stories to choose from, like how the United Church of Women, led by Ruth Rymerson, Ann Diamond, and Florence Dawson, prepared breakfast and lunch for summer school students in the kitchen of the CDCC’s Fellowship Hall. Or how a fire started in that very same kitchen in 1955 made a hero out of Richard Cowan, as he ran back into the burning building to save what he could from the flames. Or how the only reason the CDCC’s Sanctuary didn’t burn to the ground in 1955 was because of a masonry wall installed in 1946 to prevent children attending Sunday school from interrupting services with their noise. Or how Dr. Wilbur Kenneth Howard, one of the CDCC’s ministers who taught in the church’s Sunday school from 1965 to 1970, made history by becoming the first black person to graduate from the Emmanuel College theological school, and the first black person to be ordained by the United Church of Canada. These inspirational stories infuse new meaning into an otherwise inanimate building, something the symposium drew attention to.

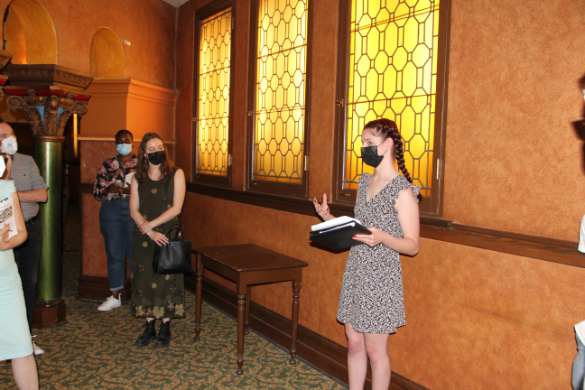

On Friday, May 13, all our hard work paid off when Carson and I gave a successful tour, despite the many headwinds we faced along the way. Working during a pandemic, travelling downtown in the midst of the convoy occupation, and trying to coordinate two busy students’ schedules was not easy, but it was worth it. Brian McDougall, an experienced tour guide and operator of the People’s History Walking Tours, even commended us on the layout and effectiveness of our tour.

I have to admit, the walking tours were my favourite part of the symposium. I especially enjoyed Glenn Crawford’s tour highlighting spaces used by members of the Ottawa 2SLGBTQ+ community. I learnt a lot about the history of my hometown that I was oblivious to before, and in an engaging, inclusive, and fun way. I remember thinking as we walked around downtown Ottawa in the heat and humidity: “now this is how you educate people!” There’s something about being onsite and learning about history in situ that reading a book can never replicate. It establishes a new kind of connection to the built environment and those who walked it before you – real people, not whoever’s version of history makes it into the books. The built environment is meaningful not just because of its materiality or the technology it contains, but because of how people use it to live their everyday lives.

The significance of our built heritage is linked to its role in creating parallel histories. Standing on the steps of Canada’s Parliament to fight for abortion rights or to demand rights and freedoms for 2SLGBTQ+ people forever changes the meaning of that space. In Lunenburg, a memorial room containing 600 hand-painted names of fishermen lost at sea connects the space with untold stories of family grief. In Montreal, modest row houses symbolize residents’ victory over the powerful interests that sought to demolish them. They are a reminder of how communities have persevered over adversity, and of the simple joy of being able to show your children the home you grew up in. Buildings are also steppingstones in the fight to decolonize our built environment through survivor-driven memorials and performances. And they invite us to unearth stories about the spaces used by marginalized groups and individuals, and to acknowledge the atrocities and efforts it took to get to where we are today.

I think that is what the history of architecture should be about. Architectural history isn’t just the buildings and people who designed them, but also the people who used them, the purpose they served – then and now. And that’s what “Small Modernisms” was all about. What an honour it was to hear speakers and tour guides touch on those hard conversations, and to participate in the re-writing of architectural history.