Africville, Nova Scotia

If you visit Africville, Nova Scotia, the first thing you’ll notice is that it’s not there anymore. Once the home of a tightly-knit community founded by black loyalists, Africville was appropriated by the municipality of Halifax and bulldozed in the 1960s. Today it’s a grassy, tree-lined park overlooking the Bedford Basin, with several recently-erected historical plaques and a reconstructed church. Traffic streaming on and off the MacKay Bridge hums in the background, and railway tracks slice the grounds into several pieces, as they have for well over a century.

When I was in high school, we were taught in history class that among the most important founders of this country were loyalists who came from the United States after the Revolutionary War and again after the War of 1812. What we weren’t taught was that many of them were black, and ended up in Nova Scotia. These Loyalists were not and still aren’t given the same degree of honour and respect. They were mostly slaves who were promised freedom in return for supporting the British side. They did, for the most part, gain their freedom, in that they were no longer legally owned. But they were sent to poor, unproductive land and given menial, low-wage work. Arguably, their quality of life was scarcely an improvement over slavery. Nevertheless, they formed vibrant, self-reliant communities with a strong sense of identity. Africville was one of these.

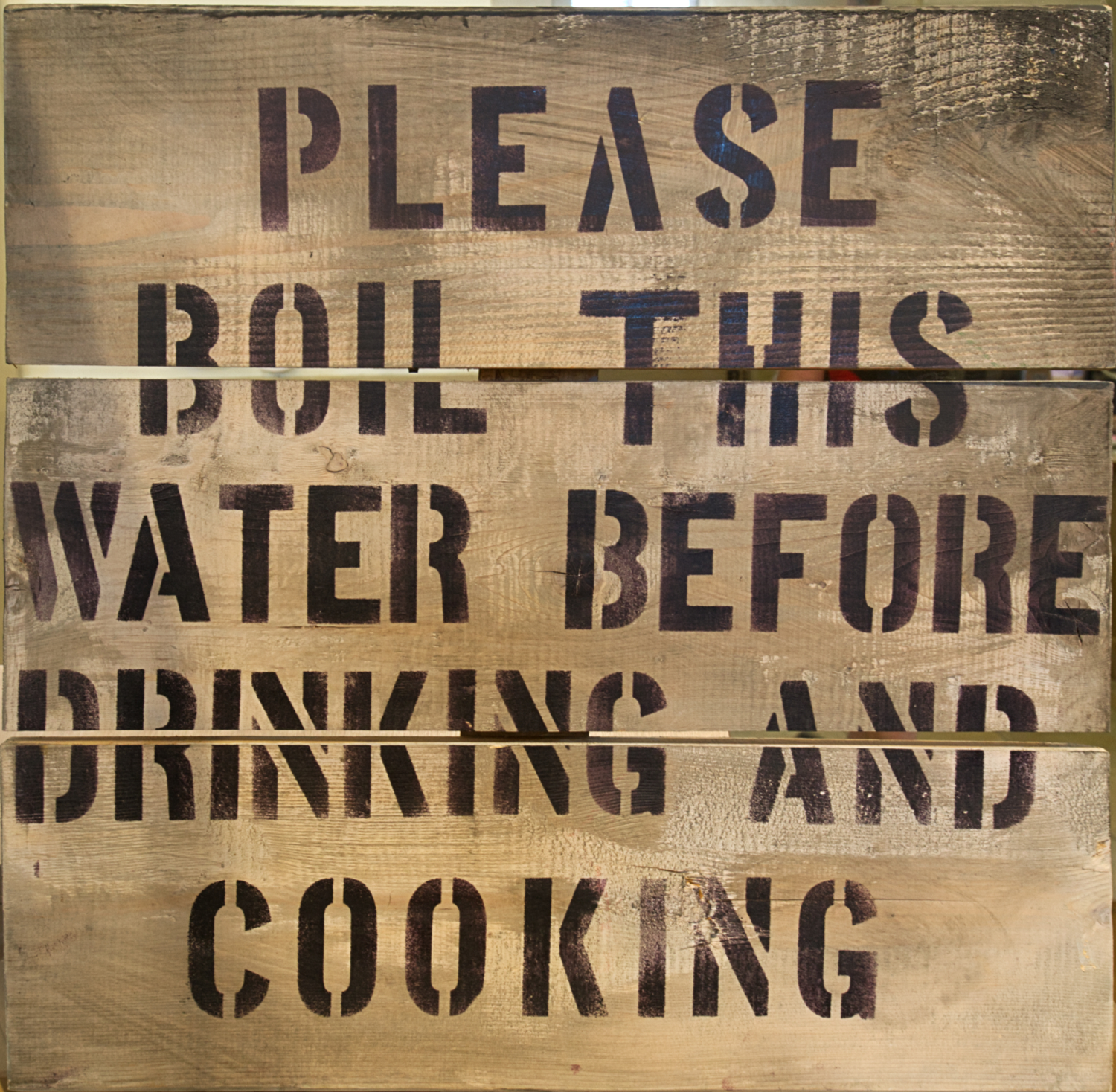

Although Africville was part of Halifax, the municipality felt no obligation to provide it with basic services. As urban infrastructure burgeoned in the later nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth, Africville was left behind. They were denied sewers, running water, garbage collection, policing and fire services. The city did build a few things on adjacent land, though: a prison, an infectious diseases hospital, a couple of slaughterhouses, and a garbage dump. The railway carved it up and wiped out several houses. Only a tightly-knit and fiercely self-reliant community could have survived this. Africville survived.

Having left Africville behind in the inexorable march of progress, the City suddenly showed an interest in the 1960s. Unfortunately, they came not to raise Africville, but to bury it. It was decided that Africville was an eyesore, the land must be appropriated, and the people dispersed. A few accepted compensation and left of their own accord. Many did not. But the City held all the cards. As one home after another was demolished, the community gradually ceased to exist. In a particularly brutal show of power and intent, the City bulldozed the church – the symbolic, social and spiritual centre of Africville – in the middle of the night on Nov. 20th, 1967.

Africvillians who opposed the relocation were met with extraordinary (but perhaps predictable) paternalism from the politicians, planners and architects of Halifax. In one television interview, mayor John Edward Lloyd used the patiently scolding tone that a father reserves for a headstrong toddler: “Sometimes, some people need to be shown that certain things are not in their own best interest and not in the best interest of their children.” I would like to think that no elected official in Canada today could get away with such a remark. But at the time, many agreed with him, and seem to have thought they were doing the people of Africville a favour by bulldozing their community and dispersing them. They failed utterly to understand what makes a community a community, and the crucial role that place plays in community identity and health. When they looked at Africville, they saw only a slum, not a home. The authorities also failed to show even minimal respect to the people of Africville, their dignity, their achievements, and the agency that everyone deserves in determining their own future.

Many displaced Africvillians ended up in a new housing development called Uniacke Square. I went to see it last summer, and was surprised by what I found. I’d expected an example of the worst kind of 1960s housing development – shoddy construction, cheap materials, and poor design. In fact, it’s a dignified and thoughtful ensemble of row houses, with attractive common spaces.

Nevertheless, it was utterly foreign to the people of Africville, how they lived, and how they interacted. It was designed by people who knew nothing about their lives, history and traditions. Moreover, it was not theirs – they’d gone from being homeowners in their homeland to being tenants in a strange place.

I was glad to have seen Uniacke Square, because it helped me to understand how some people dealing in good faith in the 1960s could have thought that the razing of Africville was a progressive move. I say this not to exonerate them, but because it helps me to realize that one can be dealing in ‘good faith’, and still be catastrophically wrong, both morally and intellectually. It is a powerful cautionary tale.

Today, nothing remains of the original Africville. The landscape has been altered beyond recognition. Landmarks like Tibby’s Pond, where generations of Africvillians waded, cooled off and learned to swim, are gone. Every building has been demolished. As a symbolic gesture of reconciliation, the City re-built the church in 2011 after years of unfulfilled promises. It serves as the Africville Museum.

As I look, listen and read about Africville, I realize I have a long way to go. To the best of my ability, I’m undertaking this project in good faith. Which, of course, doesn’t mean I won’t make mistakes and get things wrong. I’ll learn a lot, and ultimately I hope my students will too. The story of Africville is, I think, one that students who wish to be architects, planners, heritage professionals, etc. – in other words, my students – need to hear.

Peter Coffman

peter.coffman@carleton.ca

@TweetsCoffman

@petercoffman.bsky.social

Some online resources on Africville:

The Africville Museum

Africville at the Canadian Museum of Human Rights

The Africville Forever Podcast

Africville at the Nova Scotia Archives

Mapping Memories of Africville

Walking Africville Audio Tour

NFB Film: Remembering Africville

During my current sabbatical, I am gathering material from across the country for a new course we’ll be offering on Canadian architecture. I’ll occasionally use this blog to think out loud about some of the places I visit and the issues they raise.