Bridging the Gulf of Incomprehension

By Peter Coffman

During his one and only Klondike winter, writer Jack London (of Call of the Wild fame) contracted scurvy. He could have avoided it, had he consulted those who had lived in that place for millennia – the Tr’ondek Hwech’in people. They would have told him that adding spruce tea to his diet would keep him healthy during the months when fresh food was unavailable. But he never asked, because it never occurred to him that the indigenous people of the area could have anything of value to offer a modern, white, ‘civilized’ man from California.

This anecdote hints at the immense gulf of incomprehension between the Gold Rush settlers and the Tr’ondek Hwech’in – and indeed all of the indigenous peoples of the Yukon. One of the things that puts that gulf into sharp focus is the two cultures’ attitudes toward their buildings.

In my last blog, I explored several buildings erected In Dawson City between 1900 and 1902 that created what I called an ‘enclave of power’. That’s what we do in the Western tradition. We define power spatially, setting its limits with walls, fences and borders. Within those borders, we concentrate authority in certain fixed places – kings and queens have their castles and palaces, bishops have their cathedrals, CEOs have the biggest, most opulent offices, and Dawson City had its Government Reserve. This seems natural, obvious and perhaps even universal to us. But in fact it’s just a cultural norm, and not one that every culture shares. Among those who do not share it are the First Nations of the Yukon. As a result, their attitudes toward the built environment differed profoundly from those of the Klondike settlers.

The West uses architecture as (among other things) a sign of ownership and sovereignty over place. Even my own modest house proclaims “I am here. I have a right to be here that no one else has. I am going to stay here. And I can (to a point) do what I want here, because this place is mine.”

The First Nations of the Yukon had a much more immediate, intimate, and symbiotic relationship with the land than the Klondike prospectors, but none of the latter’s sense of ownership or sovereignty. For the indigenous inhabitants, the land was not something to be plundered, exhausted, and ultimately discarded. It was a nurturing entity that, treated with care and respect, would sustain them indefinitely. One result of this world-view was a completely different architecture, built for different purposes.

The Tr’ondek Hwech’in, the Champagne and Aishihik, the Kwanlin Dün and other First Nations who lived near what became the centres of the Klondike Gold Rush, were mobile peoples. They moved with the rhythms of the seasons, following the resources that ensured their survival in a harsh climate. As such, authority is not bestowed by occupation of a particular place. Homes are not centres of personal supremacy – they are seasonal habitations. When the season changes, the people will move on; when the season returns, so will the community.

The community of Klukshu (above) remains a seasonal village, filled with people when the salmon are running in the stream, emptied out when needed resources are elsewhere to be found. Historically, the ongoing priority was to gather enough food for the long winter, when fresh fruit and vegetables were unavailable, and game was scarce. The gathering and storing of food was not an individual sport. Trails were dotted with what’s know as ‘high caches’ – elevated storage rooms of food accessible to people but not animals (below). The rules for its use by those on the trail were simple: take food from the cache if you need to, leave food in it if you have extra.

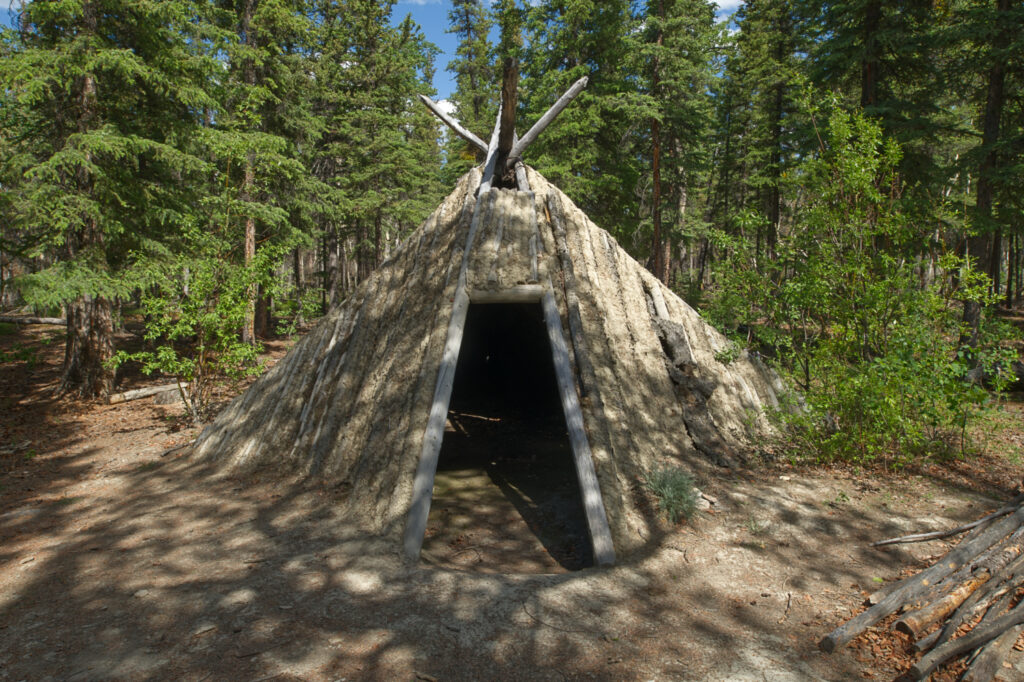

This relationship with the land gave architecture a different purpose from that in Dawson City. Unlike, say, the Commissioner’s Residence in Dawson, traditional dwellings like the one below (at the Long Ago People’s Place) do not express permanence and dominance over the land. They’re rooted in very different assumptions about why we occupy land, and what it means to do so. They express symbiosis and interdependence – take care of the land (and what it yields), and the land will take care of you. You don’t own the land – you are of the land.

We create architecture that reflects our world view and paradigms, because it’s all but impossible for us to do otherwise. By the same token, it’s impossible to understand the paradigms of others without a lot of education and effort. That’s why the Klondike settlers would have looked at indigenous architecture and seen… nothing at all. At least, nothing they were intellectually equipped to recognize as ‘architecture.’ It didn’t do what, to them, ‘architecture’ was supposed to do. It wasn’t permanent. It didn’t signify ownership. It didn’t demarcate territory. It didn’t indicate its owner’s wealth, status, or power. So, it was, to settler eyes, ‘primitive’, in contrast to their own ‘civilized’ architecture (to us over a century later, the contrast may seem more one of ‘sustainable’ vs. ‘unsustainable’).

This is the ‘gulf of incomprehension’ I refer to in the title of this blog, and it resulted in a lot of injustice as well as misunderstanding. As I inch my way up the learning curve in my education on indigenous architecture, I hope I can start to bridge that gulf in the classroom.

On the topic of indigenous architecture, histories, and cultures, I am an outsider and a beginner. I welcome your comments, thoughts, suggestions and critiques at the contacts listed below.

During my recent sabbatical, I gathered material from across the country for a new course we’ll be offering on Canadian architecture. I’ll be using this blog to think out loud about some of the places I visited and the issues they raise.

Peter Coffman

peter.coffman@carleton.ca

@TweetsCoffman

@petercoffman.bsky.social

Related Links:

Tr’ondek Hwech’in First Nation, Dawson City

Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre, Whitehorse

Da Kų Culture Centre, Haines Junction

Long Ago Peoples Place