Dredging for Dollars

By Peter Coffman

Imagine a stream cascading down a mountain, winding through a lush forest of evergreen and deciduous trees, full of moose, elk, caribou, porcupines, squirrels, and the odd bear feeding on abundant salmon.

This is what that place looks like after it has been chewed up and spat out – literally – by mining:

What beast could have wrought this change in the landscape? Introducing the dredge – specifically, Dredge No. 4, a National Historic Site just off Upper Bonanza Creek Road, near Dawson City.

A dredge is essentially a giant, mechanized gold pan. It does, at an industrial scale, what prospectors had been doing for years by hand.

Panning for gold involves scooping water and material from the streambed into a pan and swishing it around to suspend the solids in the water. The gold, being much more dense than the rock or sand (ahem – that’s ‘more dense’, not ‘heavier’, as the brochures say), sinks to the bottom. By gradually scooping out the rock and sand, the prospector reveals the gold (Full disclosure: I didn’t understand how this worked until I took part in a hands-on children’s panning activity at the MacBride Museum of Yukon History).

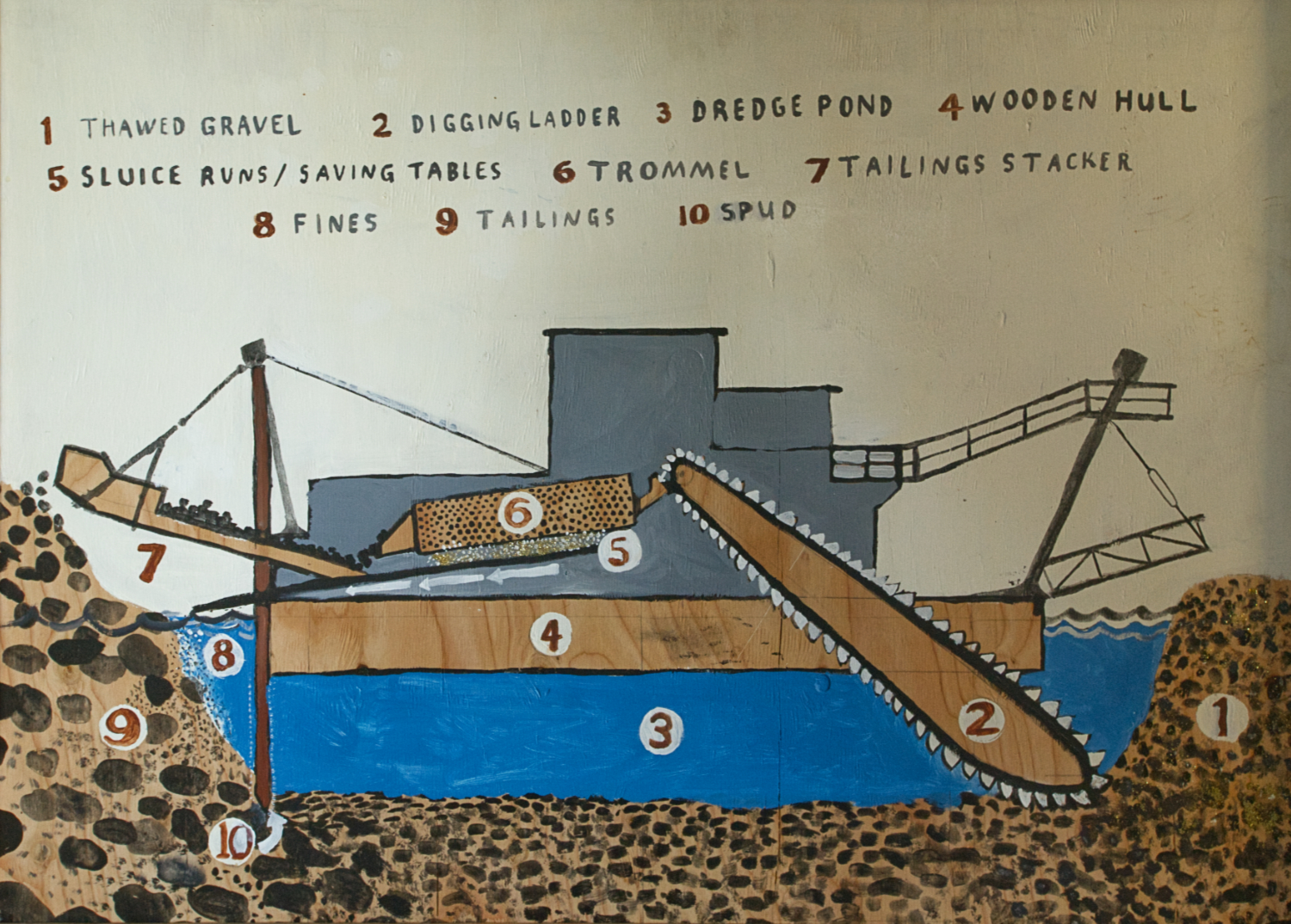

A dredge works pretty much the same way. A conveyor belt of giant shovels digs up the stream bed and hauls it into the dredge.

It’s then poured into the trommel, which rotates as jets of water are pumped through it.

The gold sinks, and is trapped in a series of sluices. The unwanted stone and sand (called ‘tailings’) is conveyed up the tailings stacker and vomited back onto the landscape.

Dredges arrived in the Yukon in 1899. That’s just three years after the discovery of gold in Bonanza Creek, and one year after the rush of thousands of fortune-seekers to Dawson City hit its peak. The days of the lone prospector with a pan, forging a path into the wilderness and (maybe) striking it rich, were already done. The most fruitful claims had long been staked, and the easily accessible gold had already been extracted. What was left (and there was still plenty left) required the muscle and deep pockets of big industry. Enter funders like the Guggenheims, and machines like the dredges.

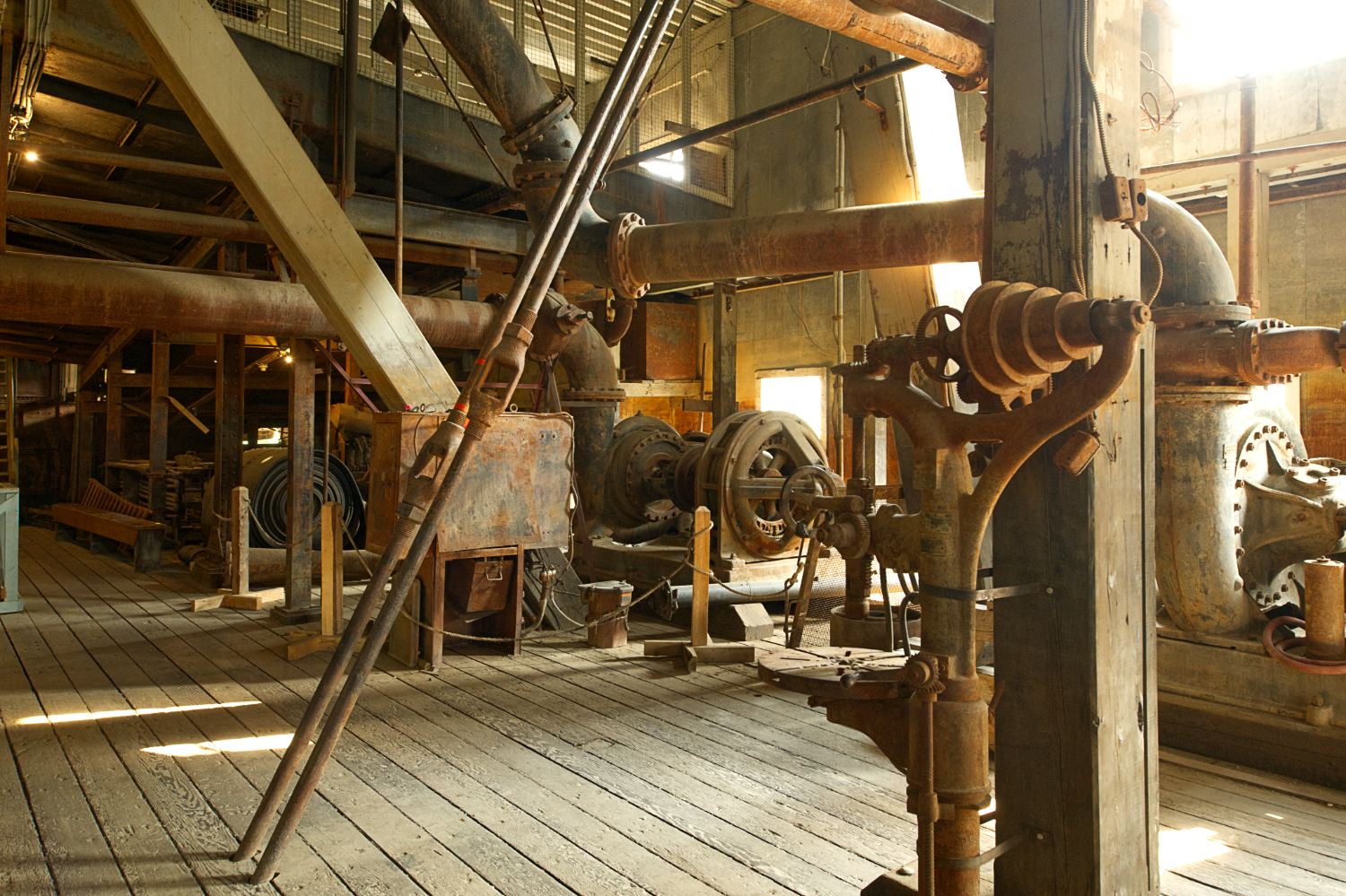

When I visited Dredge No. 4 a couple of weeks ago, I expected to see a piece of equipment. Instead, I found a monumental piece of architecture – a moveable, floating factory that devoured the landscape, digested the gold, and shat the waste out of its tail(ings) end. The sheer brute force of the thing was utterly awe-inspiring.

It’s silent now, but the noise must have been fearsome. The endless loop of giant shovels scraping up the streambed; the massive pistons, pulleys and gears churning constantly; the jets of water shooting through the trommel as the rocks bounced against its spinning sides; the mineral detritus crashing down behind the dredge and re-defining the landscape – all going on at once, 24/7.

The unmitigated power and destructiveness of this process is not pretty, but it is sublime. By that I mean what Edmund Burke meant in the 18th century – an experience of vastness, of magnificence, of light and dark, that ‘excites the ideas of pain and danger.’ It is unforgettable.

Dredge No. 4 lays bare the violence and ruthlessness with which we transform our environment for profit. Is it any wonder that that environment is reaching the limits of what it can endure?

During my recent sabbatical, I gathered material from across the country for a new course we’ll be offering on Canadian architecture. I’ll be using this blog to think out loud about some of the places I visited and the issues they raise.

Peter Coffman

peter.coffman@carleton.ca

@TweetsCoffman

@petercoffman.bsky.social

Further Reading:

David Neufeld and Patrick Habiluk, Make it Pay! Gold Dredge #4 (1994)

Dredge No. 4 National Historic Site of Canada, Canadian Register of Historic Places

John Sandlos and Arn Keeling, Mining Country: A people’s history of Canada’s mines and miners (2021)