Team Blackbird Takes Top Prize in National Student Drone Competition

Tyrone Burke

Drones have the potential to transform many important industries. Unmanned aerial systems (UAS) are being used to improve agriculture, firefighting, and wildlife monitoring. But each of these applications has different needs and comes with a unique set of challenges. Often, there is no off-the-shelf product that can solve them.

Carleton has a long history of being a leader in the field of UAS. We have both breadth and depth of expertise from our researchers and students, who are paving the way for the future of UAS in Canada and beyond.

One of the ways we demonstrates this expertise, is through our student-led unmanned air systems team, Team Blackbird.

The Power of Perseverance

Each year, the Aerial Evolution Association of Canada (AEAC) asks students from universities across Canada to solve the kind of technical challenges that need to be overcome to deploy drones in the real world. In 2023, teams were tasked to create a simulated urban passenger transportation at an airstrip in Alma, Québec. The students’ drones had to travel between multiple predetermined points to pick up and drop off simulated passengers, and plan the best possible route between these points.

Carleton University’s Team Blackbird did it better than any university in the country. It was the first time the team had won the flying phase of the event, but even though Team Blackbird ultimately prevailed, they had to overcome a few challenges to get there.

“On the first day, we didn’t even fly,” says PJ Parisien, who piloted the aircraft and led a team of more than a dozen students who contributed to Blackbird’s success this year.

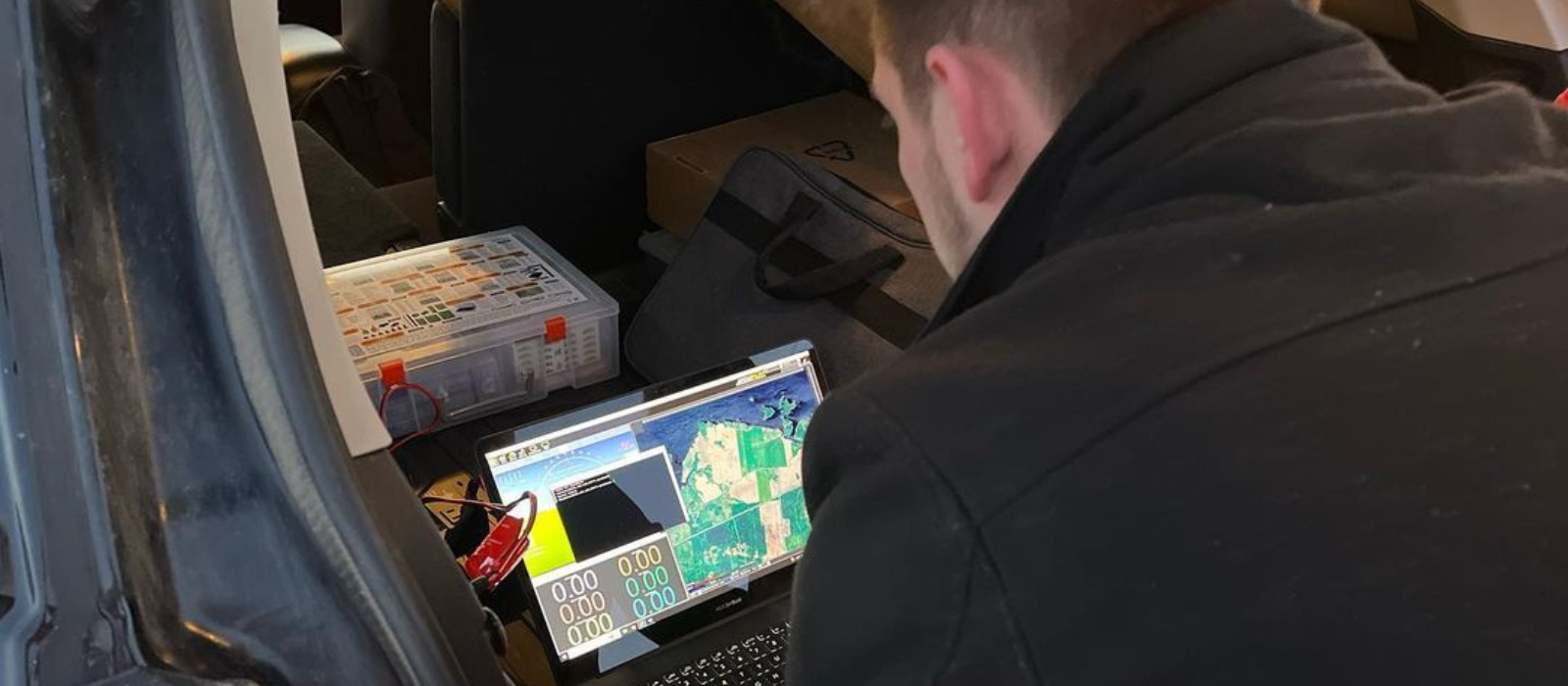

During an initial test flight, Team Blackbird identified that they were losing communication with their aircraft in one area of the airfield. One of its transmitters had inadvertently been reset, and the team had to troubleshoot the problem, but were unable to solve in time to fly that day.

Others may have been overcome by defeat at that point, but Team Blackbird was persistent. By the time they returned for the second day of competition, the conditions were favourable for success. The wind had picked up, and the team’s aircraft was a hybrid of a quadcopter and a rigid foam airplane that is well-suited to moderately windy conditions.

“The combination of a quadcopter and a plane was the perfect fit for this competition. It allowed efficiency in flight, and control on takeoff and landing,” says Parisien.

“On the second day, there were several possible routes, and our software lead, Meyiwa Jordan, wrote the code for an optimization algorithm that gave us the best one. One of the biggest challenges with this type of plane is the software. You can have the best airframe ever, but if your software is not good, you will crash anyway. We spent a lot of time tuning the software and making sure the aircraft flew in a stable way.”

Though past editions of Team Blackbird had earned podium finishes, this year’s victory was a bit of a surprise. The team was aiming to complete as many of the tasks as possible, but weren’t really thinking about winning the entire competition.

“Most of the teams achieved very little on the first day of this year’s event – including Carleton. But Carleton’s first place finish is an excellent illustration of why you never give up,” says Mark Espenant, the chief judge of the competition.

“You need to make decisions throughout, both as you are preparing and during your actual flight hours. There are many tasks and sub-tasks to complete, and you never really know whether the points from accomplishing a sub-task will be valuable or not. Despite a disappointing performance on the first day, they did the best job of managing the requirements, and achieved a significant number of the competition’s goals on the second day.”

The Legacy of Team Blackbird

Blackbird was hit hard when Carleton University’s campus was closed by pandemic-related health restrictions between 2020 to 2022. Graduating students had departed, and new students were not able to join. The team wasn’t able to get its aircraft ready in time to compete in 2022, but decided to make the drive to the competition site in Manitoba to observe the competition anyway.

That paid dividends this year. The team was able to draw on the experience during their preparations, and knew what to expect when they arrived on site. They were also able to learn from Blackbird’s past successes and failures through advice from graduate students, post-doctoral researchers and faculty, as well from an archive left by past teams.

Team Blackbird’s founders were pleased to learn of the organization’s longevity and resilience, as well as its recent success. In 2009, Kurtis Kraemer and Matthew Chiasson founded the team on a bit of a lark.

“In the beginning, Blackbird was mostly a way that I could get funding for my hobby – radio-controlled airplanes,” says Kraemer, who is now a project engineer at “De Havilland Aircraft of Canada.

“But it ended up being super valuable to my career. The experience really mimicked working in the aerospace industry. My day-to-day at De Havilland is very similar to the types of things we did on that project: managing people, applying for funding, managing a budget, and having deliverables. It is great to have programs like this, which can prepare students. Any time I talk to a university student, I really encourage them to get involved with extracurriculars.”

The team’s faculty advisor, Professor Jeremy Laliberté (who is also the Program Director for the NSERC-funded CREATE Uninhabited aircraft systems Training, Innovation and Leadership Initiative) notes that Blackbird was initially recognized for its academic value and has an ability to bring students together that reaches beyond any one discipline.

“Carleton had been doing UAV capstone projects since the late 1990s, but they are only open to fourth-year students,” says Laliberte.

“From our perspective, Blackbird was intended to be a feeder for students who wanted to do a capstone project. It was open to all undergraduates, and students in other programs. And that brings in other perspectives, especially for troubleshooting and problem solving. We have had students who study science, computer science and even art history. When a team has technical issues, everyone needs to work together to solve them, and having different backgrounds is really key.

It brings in extra perspectives, and sometimes coming from completely outside of engineering gives a different perspective that isn’t taught in an engineering course.”