Uncovering the Past

Protecting a Fading Monument of Yukon’s Forgotten Silver Rush

Ty Burke

Carleton Immersive Media Studio

In 1898, thousands of would-be millionaires flocked to the Klondike in search of gold. Yet for all its cultural resonance, the gold rush was a bit of a dud. Many miners left Yukon as quickly as they had arrived.

But some persisted, and in the decades that followed, a hard rock mining industry took root in the south of the territory. Hundreds of mines were built—and many were shuttered when metal prices plunged after the First World War. The Venus Mill site near Carcross is one of the most visible remnants of this sometimes-overlooked era of Yukon history.

Today, the mill is an accidental roadside attraction. The one-time silver mining operation on the shores of Tagish Lake was built in 1908. It operated off and on for about a decade, before being permanently shuttered in 1920. Originally accessed by boat, the Venus Mill’s remote location remained inaccessible for decades, but in the late 1970s, the Klondike Highway was built along the lake shore, bisecting the mine site. The route connected Skagway, Alaska with Whitehorse, Yukon, bringing thousands of new visitors past the mill each year–and with additional visitors came additional risks.

The mill is unstable, and slowly collapsing. And while entry is forbidden, there is no enforcement on site to stop curious travelers from venturing into unsafe spaces. The large wooden structure is also vulnerable to vandalism or arson. Compounding the risks is erosion. Hydroelectric dams caused water levels to rise, and this is undercutting the site. Part of the mill that was once on land is now partially underwater, which is accelerating decay.

With these challenges in mind, heritage conservation efforts led by Professor Mario Santana Quintero from Carleton’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (cross-appointed with the Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism) are helping the Government of Yukon create a digital record of Venus Mill that could satisfy the curiosity of potential visitors by providing insightful interpretations of the site.

“Once the highway was built, there was a lot more access and visibility, and it is concerning that people want to go in and explore,” says Rebecca Jansen, the manager of Historic Sites in Yukon’s Department of Tourism and Culture.

“By offering other opportunities for people to visit the site, we hope to mitigate safety risks, and reduce the desire to go in and check it out.”

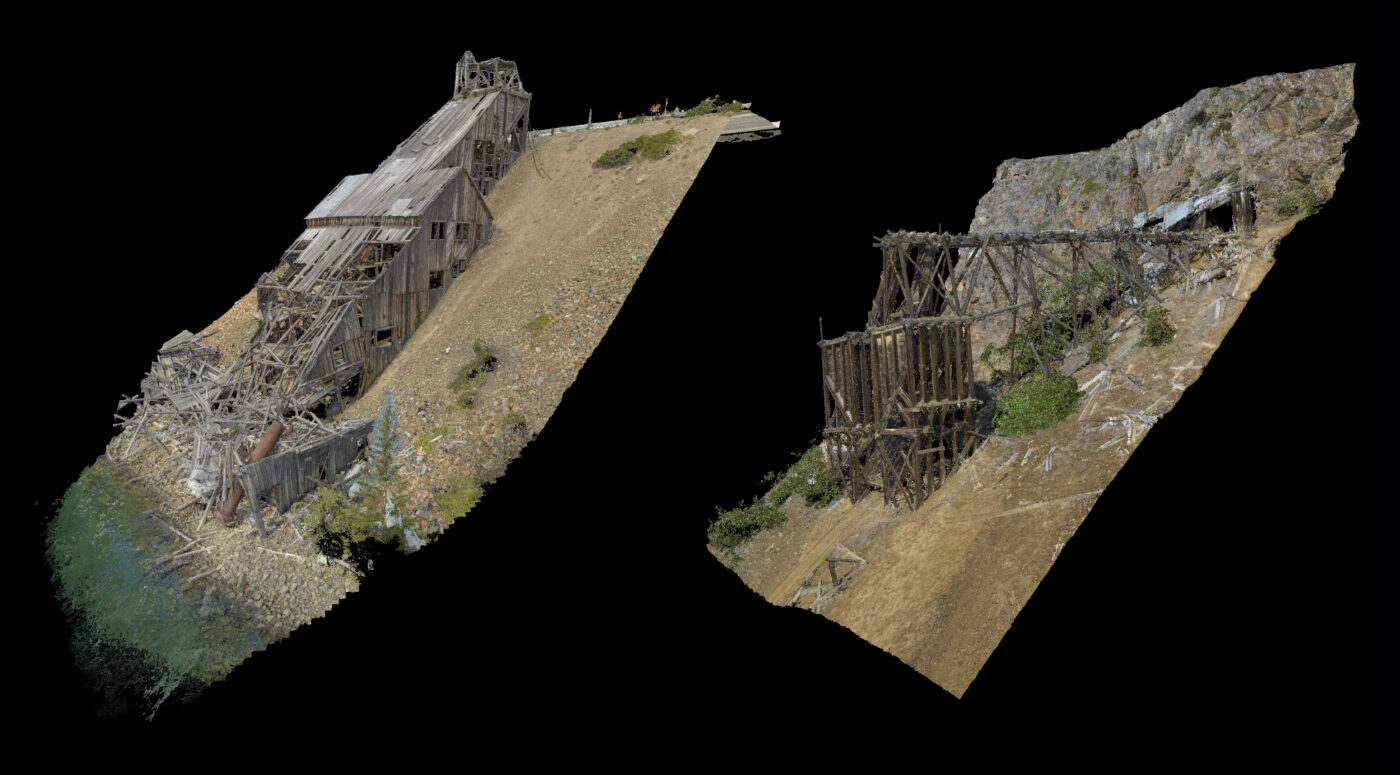

The site consists of a large mill on the lake shore, and a mine shaft further uphill. The two were connected by a 460-metre-long cable tramway that brought silver ore to the mill, where it was crushed into powder. There, it could be loaded on to steamboats and shipped to nearby Carcross, where there was a railway. But not much else is known about how the mine worked.

“The mine could collapse any minute, and restoring it would be very expensive,” says Santana Quintero.

“The Yukon government wanted to create a digital record, and based on this record, develop some kind of digital storytelling platform–the specifics of which are not yet defined.”

During the summer of 2023, Santana Quintero and a team of researchers took a multifaceted approach to documenting the site. Beneath the nearly endless daylight of a Yukon summer, they used laser-scanning technology to create a three-dimensional digital model and supplemented this with panoramic drone photography. The team did not go all the way inside the buildings but scanned the structures from the edges and made architectural drawings of the mill.

It took months to process all the data, but Santana Quintero and his team transformed it into a topographic atlas of the site that documents it in unprecedented detail. In the next phase of the project, Yukon’s Department of Tourism and Culture will collaborate with Professor Stephen Fai of the Carleton Immersive Media Studio (CIMS) to explore different ways the information might be used to share the Venus Mill site with visitors.

“In the past, critics have argued that the Yukon government hasn’t been doing enough to enhance the public’s understanding of Venus Mill, but there was also apprehension about sharing too much when we don’t know exactly what is there,” says Jansen. “We had some documentation, but no good historical photos or descriptions of how the mine operated.”

“Carleton has been an ideal partner in helping us fill in those gaps in our knowledge. This collaboration was a key opportunity to develop a detailed record of the site to dispel some of its mystery for would-be explorers and preserve this relic from another era in Yukon’s history.”

Alongside Santana Quintero, the Venus Mill Documentation project team included CIMS research leads Adam Weigert and Arkoun Merchant, and CIMS research assistants Stephanie Murray, Sena Koyunlu, Yasmine Arshad, and Ben Goforth.