Oro African Methodist Episcopal Church

In Ontario’s Simcoe County, at the intersection of Old Barrie Road and Line 3, is a modest log building that is also a symbol. It’s a symbol of freedom, or at least of the aspiration to be free. And it’s a symbol of a promise partly kept.

The original settlers here were known as the “Company of Coloured Men”. They were soldiers – black militiamen who fought for the British during the War of 1812. The reward promised them was freedom and land, both granted by the British government in this strategic area between Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe.

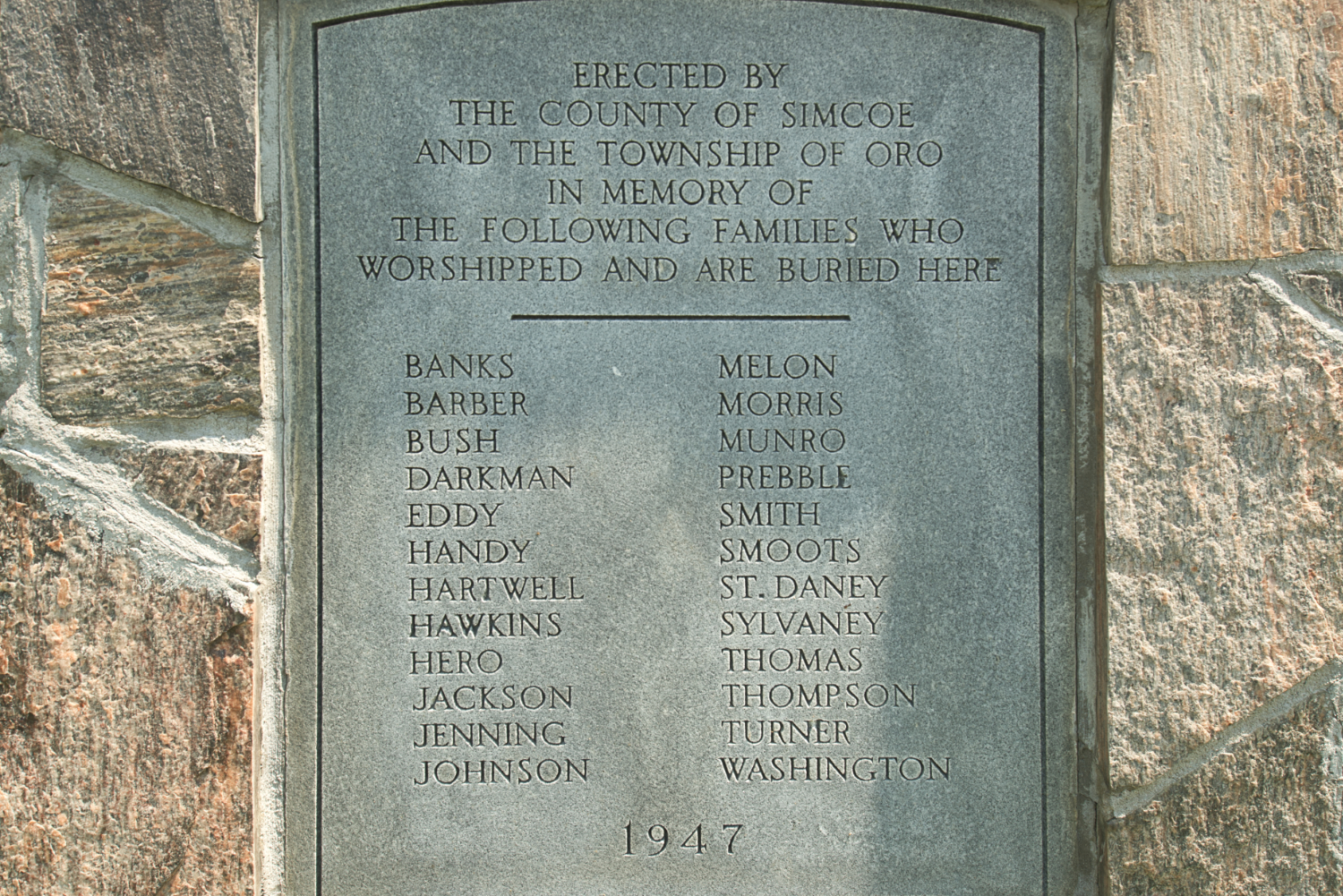

The first black soldier-settlers arrived here between 1819 and 1826. They did indeed become freemen: they were granted the same protection under the law as whites and the right to vote. Of course, genuine equality of opportunity was still a long way off (and many would argue still is). And although they were given their promised land, it was poor, remote and agriculturally unproductive land. Life here would be far from easy, but a resilient community laid down roots and, in 1847, they built this church.

As in Africville, Nova Scotia (see my blog from last week), the church became the spiritual and social heart of the community. Its extreme architectural simplicity – it could easily be mistaken for a simple log house – belies its deep importance as the heart of one of the earliest emancipated black communities in the country. That community lived, worked and died on the surrounding land. They gathered, they worshipped, they sang and they wept here. When they died, their funerals were here and they were buried under the surrounding grass. Their headstones are long gone, but the carefully manicured lawn is the community’s mausoleum, and the church is their monument.

On the one hand, the founding of the black community at Oro can be seen as another example of the government making a deal with a marginalized community, profiting from that deal, and giving up as little as humanly possible while still ostensibly keeping up their side of the bargain (or at least, meeting its minimum legal requirements). On the other hand, as landowners and citizens, the blacks of Oro had taken the first, crucial steps towards genuine equality – steps hard-earned by their service in 1812. Either way, this tiny log building encodes a lot of our history, and gives us plenty to pause and consider.

As the twentieth century dawned, the black community of Oro gradually dispersed. Unlike the residents of Africville, they weren’t forced off their land. They trickled away, presumably lured by the possibility of more opportunity elsewhere. The church was officially abandoned in 1916. It teetered on the edge of collapse (literally) for much of the second half of the twentieth century, until a fundraising campaign in 2015 raised enough to restore structural stability. It remains the last building standing to bear witness to the extraordinary community that settled here over two centuries ago.

Oro African Church could make a a fascinating and important museum, should the resources ever become available. In the meantime, it’s a remarkable and evocative place with a largely neglected history that I hope to learn more about, ideally in collaboration with my students over the next couple of years.

Peter Coffman

peter.coffman@carleton.ca

@TweetsCoffman

@petercoffman.bsky.social

Some online resources on Oro African Church:

Listing in the Canadian Register of Historic Places

Description on the Oro Medonte Township Website

CTV News Story from February 2023

During my current sabbatical, I am gathering material from across the country for a new course we’ll be offering on Canadian architecture. I’ll occasionally use this blog to think out loud about some of the places I visit and the issues they raise.