Vacation in Canada, eh? 10: The North Pacific Cannery National Historic Site, British Columbia

It was more than a factory – it was a seasonal village, where people of diverse ethnicities gathered every fishing season.

We have good reasons to choose Canadian vacation destinations these days. And we have great destinations to visit – especially if you’re interested in architecture. This is one of a series of blogs meant to shine a light on some of our built treasures.

By Peter Coffman

If visiting this remote, long-closed fish cannery isn’t on your bucket list, it should be. Okay, it’s a bit off the beaten track. If you reckon that British Columbia is all about Vancouver and Victoria, you won’t get anywhere near the North Pacific Cannery. Or even the closest town, Prince Rupert. But you’ll be missing out. This country is vast and varied, and good things await those prepared to go beyond the obvious destinations.

Once upon a time, canneries like this – over 200 of them – dotted the BC coast. They were a staple of the provincial economy. Every spring, thousands of workers poured in. Through the summer, they fished, processed the catch, ate, slept, and socialized at the cannery. In the fall, they went home, with plans to return the following year.

During the fishing season, the North Pacific Cannery became a stand-alone, self-sufficient town. It centred around its wharf and cannery building. But it also contained a wide variety of housing, a machine shop, a net loft, a general store, a laundry, and a mess hall. It had a multicultural community and a clear social hierarchy. It was a whole society, squeezed into a cannery. It was a place where people of diverse backgrounds gathered – even though, paradoxically, it was a place where they were nominally kept apart. All of this can still be experienced in the buildings of North Pacific Cannery, which opened in 1889 and became a National Historic Site in 1985.

The Cannery

The whole complex revolved around the cannery building and adjacent wharf. Fishing boats brought the catch to the wharf, where it was unloaded and moved inside for processing.

Once inside, the fish were cleaned, butchered, canned, cooked (hands up if you knew that canned fish was cooked after being canned?) and shipped to market.

All this work, from the fishing to the cooking, required a small army of workers. They came from three distinct cultural groups, each of which brought their own traditional specialty skill to the canning process. Their living spaces were strictly segregated – Indigenous on the western fringe of the complex, Chinese to the north across the train tracks, and Japanese on the east edge.

The Indigenous

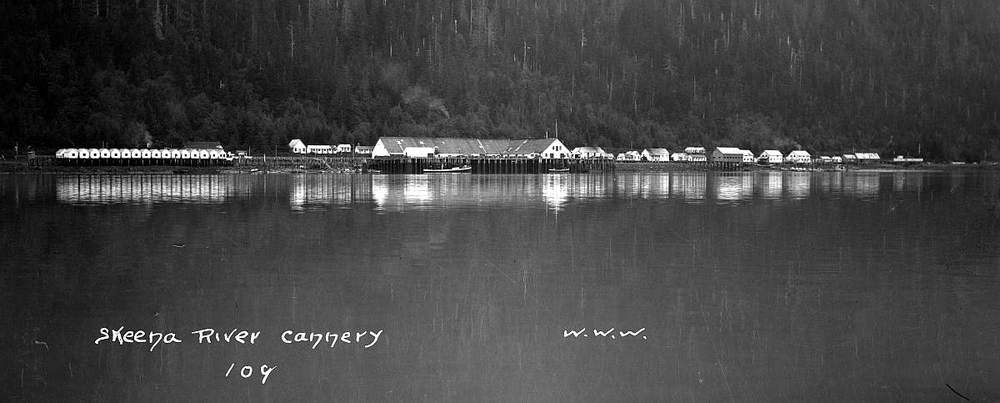

Whole Indigenous families lived and worked here during fishing season. Some were fishermen but many – especially the women – worked in the net loft maintaining the nets, without which there would be no fishery. They lived on a long, low ‘street’ (actually a boardwalk) of tiny one-room houses at the west end of the complex, clearly visible on the extreme left of this archival photo dating from 1936:

All those houses are gone, but there are plenty of photographs of them and two have been reconstructed. They give us a tangible sense of how the Indigenous families lived at the Cannery during fishing season.

The Chinese

Chinese labourers formed a large and important part of the workforce – as they did in the mining town of Barkerville, which I looked at in another blog. They too had their own housing, just across the railway tracks north of the processing building. No trace remains of it, but we can still see where they worked.

Chinese workers formed the backbone of the processing itself – cleaning the fish, trimming the meat, getting it into cans and cooking it. This happened along what was essentially an assembly line in a multi-step, labour intensive process.

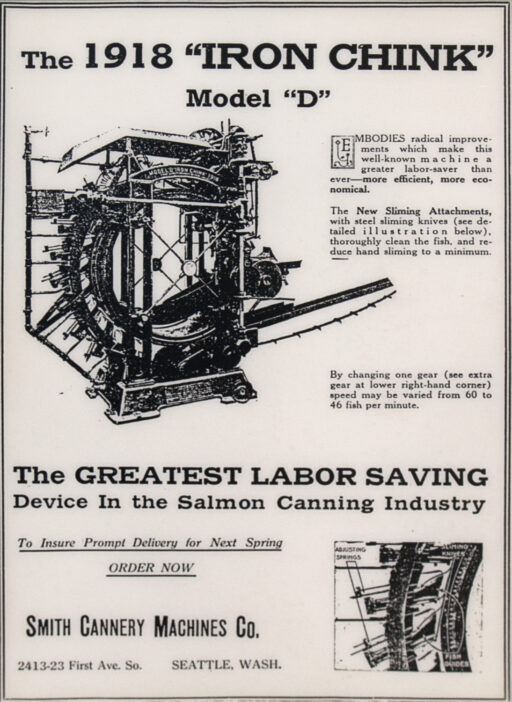

Into the 20th century, that process became more automated. Such was the prominence of Chinese workers in the canning process that the machine that replaced much of their labour was known as – brace yourself, this is ugly – the ‘iron chink’.

This racist slur says much about the crass attitude towards migrant labour common in the first decades of the 20th century. Before we get too self-righteous in our condemnation, it’s worth considering whether current attitudes toward foreign workers demonstrate much progress.

The Japanese

The Japanese workforce consisted largely of fishermen, a skill which they’d honed for generations in their homeland. They too had their own section of the complex, on the eastern fringe along the shore. Quite a bit of the Japanese area survives, and it gives us a fascinating glimpse into how the community found its place in this industrial village.

Their living quarters were very modest, but not shabby. They consisted of common areas and small individual bedrooms.

An especially interesting survival is the large shared bath, which reflects the importance of bathing and cleanliness in Japanese culture. While there’s no denying the systemic racism of the time, they were at least allowed to be Japanese (before and after World War 2 that is – during the war it was another story).

Who’s the Boss?

As is often the case, the smallest group held the power and money. And they were white. The Cannery was owned and run by men of European nationality or descent. They had their own housing in the village, and it was, unsurprisingly, larger and more comfortable than that of the workers.

What should we make of the ethnic segregation at the Cannery? There are shades of grey here. It could be interpreted as an example of the colonialist mindset exhibiting its preoccupation with keeping the races separate – a spatial expression of systemic racism. Equally, it could be considered a service to each group. Japanese workers would be immersed in a micro-community that shared their cultural practices and assumptions, ditto the Chinese, ditto the Indigenous. Of course, both of these explanations can be true at the same time. It’s clear from oral histories that the groups intermingled freely outside of their quarters, and no effort was made to prevent this.

Much as at Barkerville, economic opportunity brought people of very different cultures together at North Pacific Cannery. The nuances of their coexistence are embodied in the buildings of the North Pacific Cannery.

Epilogue

In the later 20th century, the canneries gradually vanished from the BC coast as production moved mostly to Asia. The North Pacific Cannery closed in 1981. Four years later, it was designated a National Historic Site.

For me, it’s also something of a personal historic site. My maternal grandmother, who was the daughter of Japanese immigrants, worked for a time in a cannery like this one, sometime before World War 2. I don’t know which one or what her job was, and there’s no one left alive who can tell me. But my visit to North Pacific Cannery opened a window into a part of her life that had been completely opaque to me. For all of us, it opens a window into a now-vanished way of life for generations of Japanese, Chinese, and Indigenous Canadians.

Peter Coffman, History & Theory of Architecture program

peter.coffman@carleton.ca

@petercoffman.bsky.social

Further Reading

Everlasting Memory: A Guide to North Pacific Cannery Village Museum, by Kenneth Campbell

19 Summers on the Skeena River, by Ronald Katsumi Kadowaki

North Pacific Cannery Official Website

North Pacific Cannery YouTube Site

Historic Japanese Triplexes Restored at B.C.’s Oldest Surviving Cannery, West Coast Now