Student: Lx Silver Mahr

Course: RELI2110A

Professor: Dr. Deidre Butler

Montreal Field Trip Blogs

Gender and Jewish Montreal

During our trip to Montreal, the relationship between gender and Jewish life was apparent. Our walking tour guide discussed how the wife of a poor rabbi rallied community resources to build a maternity center for Jewish women. At the time there was no dedicated Jewish hospital, leaving women with few options for healthcare. Pregnant Jewish women were reluctant and fearful of catholic hospitals, for example, where their life came second to that of the pregnancy in the event of a complication. Jewish tradition, in contrast, places the mother’s life first until birth is half complete; according to the Mishnah, abortion is required if a mother’s life at risk. Lack of kosher food in hospitals compounded these potential problems, presenting another barrier for pregnant Jewish women. The rabbi’s wife saw a need in her community that was not being met, as wefll as the high infant mortality rate at the time, and went to work collecting donations at people’s houses where she would teach. Her efforts were eventually noticed and large donors contributed to her cause. Jewish doctors volunteered their time and the center. The narrative is a good example of the general historical experience of Jewish life in Montreal and the need for Jewish women, in particular, to carefully navigate within a predominately (catholic) Christian culture. Eventually, a Jewish hospital was build and the maternity ward was named after the women who helped found the center.

The Mickvah is another important institution of gender in the Jewish community. The mickvah is essentially a religious bath, meant to restore ritual purity by full submersion in water. Women are considered to be in a state of niddah, or ritual impurity, during and seven days following menstruation and after child birth. Women are not to have sexual relations until going to the mickvah. Some orthodox communities extend this to include not being able to touch menstruating women. Due to their frequent use, mickvahs are the first thing a Jewish community builds. This is one of the only commandments directed specifically at women. Historically, in the period of the First Temple, purity laws applied to men and women. Over time, these laws eventually ceased being enforced for men. However, the institutionalization of women’s bodies through mickvah continues today. Those responsible for interpretations and decisions regarding Jewish law have been historically men, with the modern orthodox community permitting women to weigh in on these issues only within the last ten years. The stigmatization of menstruation through gendered purity laws reflects and reinforces misogynist views which, I would argue, have been engrained by and through the primary institutions which women are required to navigate. Schools are a third institution organized according to gender norms.

In our tour of Jewish Montreal we saw the location of where some schools originally stood. Prior to reforms in Quebec, there were two streams for schooling: English –protestant schools and French-catholic schools. Jews fit into neither of these categories and were thus deemed “protestant” by the provincial government and school boards. For the more orthodox community this was not good enough and went about setting up their own schools to provide a Jewish education to their children. Schools, particularly in the Hassidic and more orthodox communities, are separated by gender once children reach a certain age, generally 10 or 11. From that point, boys and girls receive a different education. Boys are immersed in the study of Torah and Talmud, whereas girls’ schooling focuses on home making skills and the obligations of a Jewish wife and mother. Though some progression has occurred, within the orthodox community emphasis lies on women occupying reproductive roles. Women are exempt from positive time bound commandments so that they are able to fulfill their duty to raise children.

Jewish Food in Montreal

Food is a large part of Jewish culture that extends beyond the stereotypical bagels and lox (though these are part of Jewish culinary choices). Many Jewish foods carry a rich history and symbolism. Montreal has a thriving Jewish culinary scene that has influenced the city in important ways. When one thinks about Montreal food, smoked meat, kosher delis and Montreal style bagels are some of the first things that come to mind. Many of the Jewish foods that have become synonymous with Montreal foods hail form Ashkenazi roots. These roots stretch back to central and Eastern Europe. Jewish immigrants brought with them their culinary traditions from homelands and incorporated them into the city’s landscape.

Jewish laws surrounding food and keeping kosher are extensive. Food is split into three categories: dairy, pareve and meat. Pareve foods can be eaten with both dairy and meat. Pareve foods include all plant-based foods, fish and eggs. Dairy and meat cannot be mixed, as you are not allowed to cook a kid in its mother’s milk; only fish with both fins and scales are permitted. Furthermore, shellfish and reptiles are not allowed. Only animals with split hooves that chew their cud are permitted (e.g., sheep and cows). Animals must be slaughtered according to shechita which is performed by slitting the animal’s throat with a sharp, non-serrated blade. It is done quickly and without hesitation to minimize the animal’s suffering. Separate pots and plates are to be used for dairy meals and meat meals. Keeping kosher as a Jew in Canadian society provides an immediate challenge; accessibility and variety of kosher products can be extremely limited. Keeping kosher therefore required Jews to build their own community and live close to one another so that they can set up kosher infrastructure such as butcher shops and delis. The limitation of being unable to eat at non-Jewish houses helped to insulate the community, thus helping further deter from inter-faith marriage, which is still an important issue within the Jewish community as well as being banned in the Talmud.

It is very important for Jewish people to create geographically close, tightknit communities. Until the creation of Israel, the Jewish experience was typically defined by dysphoria under either Christian or Islamic rule. This was a driving factor in the creation of communities within a society that they felt differed from their own. Practices surrounding the customs and laws of Sephardic and Ashkenazi food, as well as the types of each food, also differ greatly. Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews were both influenced by their location, as well as the cultures that they were surrounded by. Ashkenazi food is similar to that of Eastern Europe, while Sephardic food shares more in common with dishes from Northern Africa. There are also culinary differences in what is considered kosher for Passover. Sephardic Jews, who would have traditionally eaten much more rice than Ashkenazi Jews, would have considered rice a kosher dish for Passover. Contrary to this, Ashkenazi law was much more restrictive.

Scandals have plagued the kosher food industry. For example, it is illegal to label a food as kosher if it is not. There have been investigations at kosher slaughterhouses, as well as public outcry, regarding the welfare of the animals involved at these alleged kosher locations. The process of kosher slaughter makes it hard to industrialize, and requires immense time and resources to be done properly. Furthermore, many attempts to industrialize the slaughter process have been prevented by different animal rights groups. They do not stun the animals before they kill them, something that is common practice in non-kosher and non-halal slaughterhouses. The absence of stunning has been criticized by animal rights activists as cruel. Jewish and Islamic groups have responded by calling these characterizations representative of anti-Semitic (or Islamaphobic) sentiment, maintaining that it is not cruel to the animal when done properly.

Jewish diversity

Jewish diversity is as rich as the history of the Jewish peoples. There is a split between Ashkenazi Jews, who originate from central and eastern Europe and throughout history lived under the influence of Christianity, and that of Sephardic Jews originating from Spain, Portugal and north Africa and whose historical experience has been under the rule of Islam. Within the Ashkenazi community there is further division among orthodox, conservative and reform groups. This ideological fragmentation does not occur within the Sephardic community. Sephardic Jews’ practice would most resemble the Ashkenazi orthodox movement.

The Hassidic community, on the other hand, fiercely rejects modernity in all forms, living for the most part and dressing in the same fashion that the eastern European communities they descend from hundreds of years ago would have. The Hassidic movement arose as a confrontation to rabbinic Judaism. This movement emphasised joy as a way to be closer to god and that there is spirituality to be found everywhere, even in the mundane. The Hassidic community is unique in that it has a Rebbe, a pious man who is the leader of the community and to whom people consult when seeking answers to life’s questions. The Rebbe’s successor is often a close relative or favourite student (usually both), creating and perpetuating dynasties. Some Rebbe’s have been thought to be the messiah by their followers who make pilgrimages to their graves, thus creating divisions within the Hassidic sphere. Hassidic communities historically migrated to North America while fleeing persecution and have since strongly rejected assimilation. Montreal is home for a large number of Hassidic Jews who have carved out neighbourhoods for themselves and shaped the city in important ways.

The ideological split within the Ashkenazi community has its roots with Jewish Enlightenment, or haskalah. Its goals were to reform Jewish life and redefine the Jewish peoples’ relationship with the state. The enlightenment era ushered in new schools of thought and rejected the immediate past of the dark ages. It piloted ideas about the state and citizenship, as well as individualism and scientific empiricism. Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786), a German enlightenment philosopher, is credited with having started the haskalah movement. Mendelssohn tried to reconcile modernity with the Jewish faith and enlightenment ideas, stating that there was no conflict between them. He saw Judaism as non-dogmatic, logical, and conducive to modernity. He advocated for educational reforms and the removal of civil disabilities for the Jewish community. His ideas spread across Europe and created a split within the Jewish community: those who believed in the blending of modernity and Judaism, and those who rejected modernity and clung to tradition. Abraham Geiger (1810-1874), a German rabbi, is considered the founder of the Reform movement. His argument was that Judaism had always evolved and thus should continue to evolve in the face of a rapidly changing society. Canada’s Jewish demographic is considered to be more conservative than its American counterpart. Even Canada’s Reform movement is seen widely as more conservative, having stronger beliefs surrounding intermarriage and recognizing children of intermarriage as Jewish.

Close up of the sign on the door.

Hassidic synagogue exterior.

During our trip we were able to see the Hassidic community courter and a Sephardic synagogue. A visually sharp contrast exists between what was pointed out to be a Hassidic synagogue and that of the Spanish and Portuguese synagogues. The Hassidic building tried very hard not to draw attention to itself, marked only by a piece of paper with Hebrew script taped to the door. In order to recognize what these buildings were, one would require to be an insider of the community. The Hassidic community is marked by their rejection of modernity which, for the most part, isolates them from the people and communities outside their insider groups. A strict way of life requires specialty shops. For example, we saw storefronts with mannequins dressed in very modest dresses, clearly intended for the Hassidic or Orthodox shopper. I somewhat felt the feeling of being an outsider walking through the Hassidic community. In the dairy restaurant we stopped at, two young girls around 7 or 8 years old where speaking Yiddish to each other while starring at my shoes (they where chucky white leather loafers, so perhaps warranted). I couldn’t help but think about how different my childhood and theirs must be.

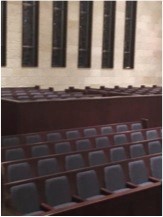

The main sanctuary of the Spanish and Portuguese synagogues.

Exterior of Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue.

The Spanish and Portuguese synagogue is an over 200-year-old congregation that has moved buildings several times over the course of its history in order to accommodate its followers. I had personally never been in a Sephardic synagogue, or any synagogue which men and women sat in separate places. We saw three different sanctuaries within the synagogue, each room addressing this separation in a different way. The first one we saw was one that was used for daily prayers and was being used at the time for evening prayers. This room addressed the issue of separate seating in the most egalitarian way out of the three. Women sat in the middle section and men sat at the sides. There was no formal barrier of division. The second room we saw was a lesser used room, which was the Ashkenazi room. This room had the men siting around the podium and the women were seated far behind them separated by a metal barrier. The effect was that the women had no direct line of sight, only able to hear the proceedings. The last sanctuary we saw was the largest, blending the approach to women’s seating from the previous two. Women still sat at the sides in the back, but were separated by a low barrier creating a division that did not block the line of sight. It was interesting to compare the different ways the separation of men and women were architecturally addressed in each room. I had also never seen a Sephardic Torah, so I found that interesting.

Division of seating between men and women in the main sanctuary.

Sephardic Torah.