By Lesley LeRoux, TLS freelance writer

While some might call a lesson in mathematics boring, others see it as a performance, capable of engaging an audience of undergraduates as if they were watching an engrossing film.

Such is one of the discoveries from Carleton linguistics professors Natasha Artemeva and Janna Fox’s research on how mathematics is taught in undergraduate classes around the world.

The goal of the study, which began in 2007, is to inform requests to change mathematics teachings at the elementary and secondary school levels to better prepare students for university.

“We think there’s such a drastic difference between how mathematics is taught in schools and how it is taught in universities. For students, it’s simply like walking into a course that’s taught in a foreign language they don’t know,” Artemeva says. “This is too bad, because university mathematics is taught to train students, to make them into apprentices in the mathematical discipline, and apparently what schools do is something different.”

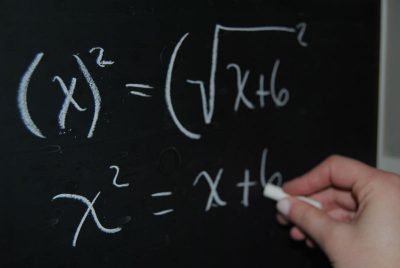

The researchers used video cameras to record mathematics lectures after finding that instruction in the discipline is highly visual. Fox says they took a multi-modal approach, taking into account textual, auditory, and expressional cues, such as movement and gesture.

What they found was that mathematics was taught in strikingly the same way wherever they went, regardless of language, country, culture, or whether instructors were teaching in their first or second language.

Artemeva says she and Fox coined the term ‘board choreography’ in their study to describe how instructors write on the board in real-time and simultaneously explain what was happening on the board.

“Professors even think in advance what they’re going to write on which part of the board, and what they’re going to erase and what they’re going to keep because it will become important later in the lecture,” Artemeva says.

These discoveries are significant for the next phase of their research, when they explore how different lecture formats affect students, whether it’s a face-to-face class, a video-recorded lecture, an online course, or a discussion group.

Fox says this further research is important to help students who are not mathematicians succeed in mathematics courses that are taken as electives.

“For a long time, we’ve needed to understand what makes it work for students in those classes and how we can make it function better to support greater academic success,” Fox says. “So it’s very rewarding to be working in an area where you might be able to do some good.”